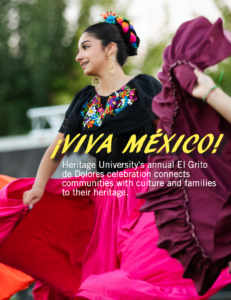

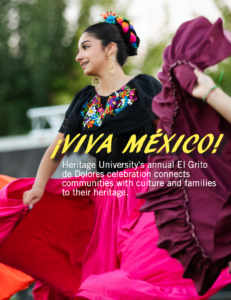

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

“¡Mexicanos! ¡Vivan los héroes que nos dieron patria! ¡Viva Hidalgo!,” he called out.

“¡Viva Hidalgo!” the crowd responded.

“¡Viva Morelos!,” he cried. The crowd called back, “¡Viva Morelos!”

Back and forth they went, the official crying out and the crowd responding:

¡Viva Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez!

¡Viva Allende!

¡Vivan Aldama y Matamoros!

¡Viva la Independencia Nacional!

Until the call reached its crescendo.

Vendors sold everything from handmade traditional crafts to authentic Mexican foods.

“¡Viva México! ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México!”

The official rang a bell and waved the flag while the crowd cheered. Then, all raised their voices and sang the Mexican national anthem.

“Mexicanos, al grito de guerra el acero aprestad y el bridón. Y retiemble en sus centros la Tierra, al sonoro rugir de el cañón,” the song begins.

The crowd was a sea of emotion. Elderly men and ladies stood with their backs pencil straight, tears streaming down their faces, hands held across their chest in the saludo a la bandera. Parents’ attention was momentarily drawn from their playing children as they were swept away by the moment. It was one of those rare moments when pride, respect and unity were so palatable that they seemed to hang in the air.

This was El Grito de Dolores at Heritage University.

PRIDE AND PATRIOTISM

El Grito de Dolores is for Mexico and its citizens what the 4th of July is for the United States. It commemorates the events that sparked the Mexican War of Independence.

In the middle of the night on September 16, 1810, in the city of Dolores, Mexico, Roman Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla rang the church bell, calling his congregation to assemble. He addressed the crowd, urging them to revolt against Spanish rule. His speech sparked an 11-year war in which Mexico gained independence from Spain. Every year, on September 15, at 11:00 p.m., Mexico’s president reenacts the cry from the balcony of the National Palace in Mexico City. The call is simultaneously reenacted in cities and towns, large and small, throughout the country, with each community’s highest-ranking official serving in the place of the president.

Jennifer Renteria-Lopez

“Of all the cultural activities that take place in Mexico, El Grito is one of the most significant,” said Jennifer Renteria-Lopez, director of Heritage University’s High School Equivalency Program and one of the lead organizers of the university’s El Grito celebration.

“For Mexicans, it means we are our own people. We are a single, independent country in control of our own government and direction.”

El Grito brings together communities for celebrations that last for days. There are parades, carnivals, Banda music, street dances and food, lots and lots of food. It’s a whirlwind of color and sounds that culminates with the late- night reenactments.

Once this young celebrator got the mic, there was no getting it back from him.

CONNECTING PEOPLE TO CULTURE

For people of Mexican descent, like Renteria-Lopez, living in the Yakima Valley, distance and time often lead to a disconnect from their cultural roots. Renteria-Lopez was born in the United States but was taken to Mexico by her mother when she was just three months old. She lived there submerged in her culture until she and her now husband moved to the US when she was 19 years old.

“We were searching for a better life,” she said.

Like so many Mexican nationals who immigrated to the Yakima Valley, Renteria- Lopez came to the country with a strong work ethic but limited English skills. She learned about Heritage’s HEP program, where she could take English as a Second Language (ESL) classes and earn a G.E.D. She enrolled and became so connected to the program that she continued to take ESL classes and volunteered to help other students long after she graduated. Before long, her volunteer work turned into a paid position. Her academic journey also progressed.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

Renteria-Lopez and her husband built a good life for themselves and their little family which includes two young daughters. However, the longer they lived here in the United States, the more disconnected they became from their cultural heritage. They found themselves spending more time celebrating the customs and holidays of this country than those of the country where they were raised and where much of their family still lives.

The face painting booth was one of the most popular activities.

“We left behind everything when we came to the United States, even our culture,” she said. “When you immigrate to a new country, you are an outsider. You want to fit in with your new home and the people who live here, so you set aside part of yourself and adopt the culture of those in your new home. You walk between two cultures. You are not American or Mexican; you’re a little of both.”

Her story, she said, is not unique. As life gets busy and families integrate into their communities, it is easy to lose sight of traditions, especially for things like El Grito that involved whole communities celebrating in unison, and where there are no such celebrations in your adopted country.

Five years ago, when Heritage’s president, Andrew Sund, announced the university would be hosting an El Grito celebration on campus, Renteria-Lopez signed up to be part of the planning committee.

Young dancers from Grupo Vicio

performed Mexican folk dances.

“There was nothing else like this in the Yakima Valley,” she said. “You’d see Cinco de Mayo events, but those are not as culturally significant as people think they are. They are an Americanized version of a Mexican holiday that is really only celebrated in one region of Mexico.”

El Grito, however, is immensely significant. It’s a point of national pride that involves every citizen in every state, city and town. It is part of the cultural fabric of the nation. And, bringing it to Heritage was huge, she said.

“I’ve lived in the United States for 17 years. This was the first time since I left Mexico that I was able to celebrate El Grito and the first time my children have been able to connect to this part of their cultural heritage,” she said.

Gerardo J. Guiza Vargas from the Mexican Consulate in Seattle performs the El Grito de Dolores.

Renteria-Lopez has been part of the planning committee every year since El Grito was first celebrated at Heritage in 2019. This year’s event brought more than 800 people to the Heritage campus. Children made crafts and got their faces painted. Families played games together, including loteria, a traditional game much like bingo, danced to Banda music, and ate authentic Mexican food before the culminating Cry of Delores.

“It was such an emotional experience, being here on the campus, with others who, like me, have lost touch with this part of themselves, and being part of the team that brought El Grito to the Yakima Valley,” said Renteria-Lopez. “I am very proud of being part of this experience and proud that Heritage is giving Mexican Americans the opportunity to celebrate their heritage and share it with the rest of the community.”

The Heritage family lost a beloved member this summer when Jim Barnhill passed away in August. He was 92. Barnhill’s connection to Heritage and its students went back to the university’s infancy. For 36 years, he and his wife Dee, who preceded him in death last year, provided philanthropic support for student scholarships and campus development. They established the Jim and Dee Barnhill Scholarship in the mid- 1990s, an endowed fund that will support students in perpetuity. Additionally, they were lead supporters of the construction of the Arts and Sciences Center, as well as the construction of five buildings built between 2015 and 2018, one of which houses The Barnhill Fireside Room, named in their honor.

The Heritage family lost a beloved member this summer when Jim Barnhill passed away in August. He was 92. Barnhill’s connection to Heritage and its students went back to the university’s infancy. For 36 years, he and his wife Dee, who preceded him in death last year, provided philanthropic support for student scholarships and campus development. They established the Jim and Dee Barnhill Scholarship in the mid- 1990s, an endowed fund that will support students in perpetuity. Additionally, they were lead supporters of the construction of the Arts and Sciences Center, as well as the construction of five buildings built between 2015 and 2018, one of which houses The Barnhill Fireside Room, named in their honor. Well-loved Yakima Valley philanthropist and long-time Heritage University supporter Marie Halverson passed away on October 21. She was 90 years old.

Well-loved Yakima Valley philanthropist and long-time Heritage University supporter Marie Halverson passed away on October 21. She was 90 years old. Tragedy struck the Heritage family on October 15 when student Aspen Hart passed away from injuries sustained in a car accident. She was 18 years old.

Tragedy struck the Heritage family on October 15 when student Aspen Hart passed away from injuries sustained in a car accident. She was 18 years old.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.