Martin Valadez promoted to Vice President for Strategic Initiatives at Heritage University

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Martin Valadez promoted to Vice President for Strategic Initiatives at Heritage University

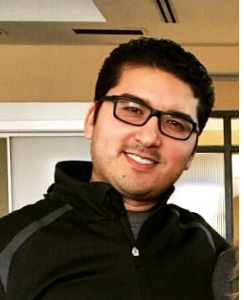

Toppenish, Wash. – Heritage University President Andrew Sund, Ph.D. announced on July 13, 2023, the promotion of Martin Valadez from director of the Heritage University Regional Site in the Tri-Cities to Vice-President for Strategic Initiatives at Heritage University. In this role, Valadez will oversee university operations at its new regional site in downtown Kennewick, Wash. and at its branch campus at Columbia Basin College in Pasco, Wash. as well as take a leadership role in developing additional strategic initiatives for the university.

Valadez joined Heritage University in 2019 as the director of the newly formed Workforce Training and Education program known as Heritage@Work. A year later, Valadez was selected to become the director of Heritage University’s Tri-Cities branch campus at CBC. Valadez has lived in the Tri-Cities since 2006 and is an active leader in the area’s academic and business communities through his experience at CBC as a professor and as the VP for Diversity and Outreach. He also has strong business connections through his work as the former CEO for the CBC Foundation and as a member and vice chair of Gesa Credit Union board of directors. Valadez also recently returned to his role as president of the Tri-Cities Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, where he has served in various roles for more than 13 years. He is also a board member of the Tri-Cities Economic Development Council (TRIDEC); on the board of directors of the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC); and current Chair of the Mid-Columbia Libraries board of trustees.

Dr. Sund says the adaptability and flexibility shown by Valadez when taking on new roles make him the perfect choice to develop and foster new projects for university growth. “Valadez has a proven track record with delivering consistent results and achieving targets in every venture,” Sund said. “He has shown an ability to grow positive relationships with clients, partners and colleagues which enhance Heritage’s reputation and drives growth. This promotion is a result of his exceptional work and in recognition of Martin’s service to Heritage University.”

Valadez expressed gratitude for this recognition of his contributions to the University thus far and the opportunity to contribute in a larger role. “Heritage has been changing the trajectory of students’ lives for more than 40 years and it is an honor to be a part of an organization that is 100% mission driven.”

Valadez officially started his new role as VP of Strategic Initiatives on July 1. For more information, please contact Davidson Mance at (509) 969-6084 or mance_d@heritage.edu.

# # #

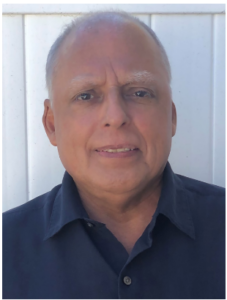

Mike Villarreal (M.Ed., Educational Administration) was elected to serve as president of the Washington Association of School Administrators for the 2002-23 academic year. Villarreal is the superintendent of Hoquiam School District, a position he’s filled since 2017.

Mike Villarreal (M.Ed., Educational Administration) was elected to serve as president of the Washington Association of School Administrators for the 2002-23 academic year. Villarreal is the superintendent of Hoquiam School District, a position he’s filled since 2017.

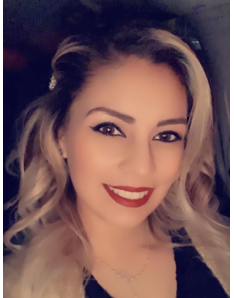

Francisco Ramirez-Amezcua (B.A., Environmental Studies) is a migrant graduation specialist at Sunnyside High School. This past fall, he was awarded Student Support Staff of the Year for the Sunnyside School District.

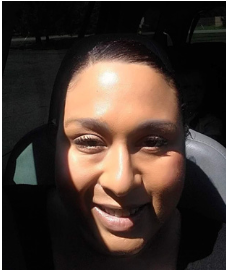

Francisco Ramirez-Amezcua (B.A., Environmental Studies) is a migrant graduation specialist at Sunnyside High School. This past fall, he was awarded Student Support Staff of the Year for the Sunnyside School District. Dalia Chavez (B.A., Criminal Justice) joined the Washington State Human Rights Commission (WSHRC), where she serves as a civil rights investigator based in the Yakima Valley. The WSHRC is a state agency responsible for administering and enforcing the Washington Law Against Discrimination.

Dalia Chavez (B.A., Criminal Justice) joined the Washington State Human Rights Commission (WSHRC), where she serves as a civil rights investigator based in the Yakima Valley. The WSHRC is a state agency responsible for administering and enforcing the Washington Law Against Discrimination.

“I had worked with students and families one- on-one,” he says. “Instead of touching lives one at a time, I wanted my work to have a positive effect on as many people as possible, to do things on more of a macro instead of a micro level.”

“I had worked with students and families one- on-one,” he says. “Instead of touching lives one at a time, I wanted my work to have a positive effect on as many people as possible, to do things on more of a macro instead of a micro level.”

“Students will have the opportunity to transfer seamlessly between campuses, and some classes may be offered in a hybrid format where classes are delivered both in-class and online between the two campuses. The linkage between the two campuses will present a tremendous range of possibilities for students to study in their field of interest,” said Sund.

“Students will have the opportunity to transfer seamlessly between campuses, and some classes may be offered in a hybrid format where classes are delivered both in-class and online between the two campuses. The linkage between the two campuses will present a tremendous range of possibilities for students to study in their field of interest,” said Sund.