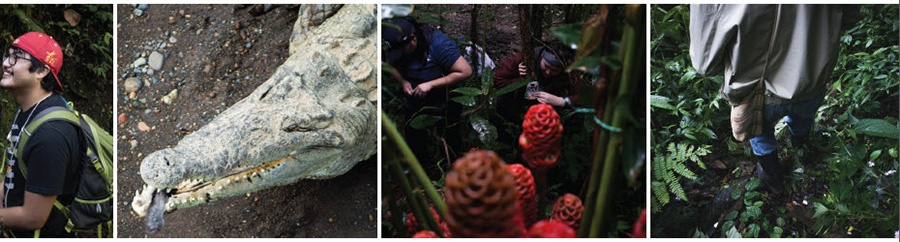

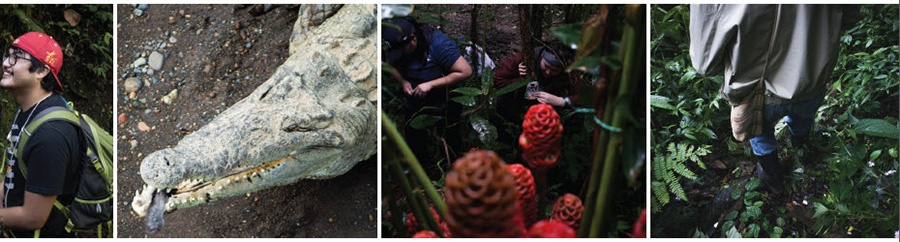

In a balmy rainforest in Costa Rica, frequented by big cats, poisonous snakes, screeching monkeys and exotic fauna, four students from Heritage hiked along dirt paths, collected water and plant samples, set up wildlife tracking cameras, and had the experience of a lifetime over winter break. The reason they traveled so far on their time off from school was to conduct environmental and biological field studies at the Las Cruces Biological Research Center, about three miles from the Panamanian border. Founded in 1962 as a botanical center and nursery, it is the home of the Wilson Center, the country’s best-known botanical garden. In 1973, it expanded its emphasis to include tropical research, particularly in conservation.

Steve Dupuis, the IMSI director at Salish Kootenai College in Pueblo, Montana, reached out to Dr. Jessica Black about the trip, which he had done the year before. It was structured to bring tribal students in the sciences together from colleges across the country. Heritage University’s participation was made possible by a partnership with the All Nations Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation program, in conjunction with the Organization for Tropical Studies.

Steve Dupuis, the IMSI director at Salish Kootenai College in Pueblo, Montana, reached out to Dr. Jessica Black about the trip, which he had done the year before. It was structured to bring tribal students in the sciences together from colleges across the country. Heritage University’s participation was made possible by a partnership with the All Nations Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation program, in conjunction with the Organization for Tropical Studies.

“Research shows that when students are given the chance to travel internationally for study abroad experiences, it has a profound impact on their academic performance, empowering students as they work towards completion of their degrees and ultimately leading to higher GPAs,” said Black. “It’s something we were really lucky to do, and my hope is that it will become an annual event for our Native American STEM majors.”

Kimberly Stewart and Zane Ketchen were two of the students invited to travel to the Central American country. When Stewart received the text from Black, she was immediately intrigued – not just about the chance to dig into field work in such a rich environmental location but also because she would meet and work with other Native American students from around the country. “I had traveled, but never to Central America,” said Stewart, a junior who is interested in working with the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources when she graduates. After an 11-hour flight to San Jose, the team hopped aboard a bus for the six-hour journey into the Talamanca Mountains the next day. Taking the coastal route, Ketchen had his first look at Costa Rican wildlife, including crocodiles, macaws, and Black’s favorite, the toucan!

Kimberly Stewart and Zane Ketchen were two of the students invited to travel to the Central American country. When Stewart received the text from Black, she was immediately intrigued – not just about the chance to dig into field work in such a rich environmental location but also because she would meet and work with other Native American students from around the country. “I had traveled, but never to Central America,” said Stewart, a junior who is interested in working with the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources when she graduates. After an 11-hour flight to San Jose, the team hopped aboard a bus for the six-hour journey into the Talamanca Mountains the next day. Taking the coastal route, Ketchen had his first look at Costa Rican wildlife, including crocodiles, macaws, and Black’s favorite, the toucan!

FIELD WORK GIVES STUDENTS HANDS-ON RESEARCH SKILLS

FIELD WORK GIVES STUDENTS HANDS-ON RESEARCH SKILLS

The students faced a much different culture and climate in Costa Rica. The weather was more humid than at home. the hikes were challenging, long and windy, up steep and muddy paths. And, the wildlife! Ketchen recalls stumbling across snakes on several occasions, and one was the fer-de-lance – a deadly pit viper!

The research projects pushed all the students out of their comfort zone, in a good way. There were 14 participants from all the colleges involved, and they met as a group to brainstorm about potential projects. From there they whittled down a whiteboard of ideas to a few, and students could self-select the one they were most interested in: invasive species, water quality or botany. They spent most days in the field and then summarized their findings in a poster and presentation at the program’s conclusion.

Stewart and Corbin Schuster, who graduated this year with a B.S. in Biomedical Science, chose an invasive species project. Their team measured the severity of a plant fungus to determine if humidity levels contributed to its spread. They took samples from different elevations and used software to calculate the area of each leaf that was compromised. Stewart is excited to continue with research in the next phase of her education. “I’ve been nervous about going to grad school,” she admitted. “Now I feel certain I can do it.”

Ketchen and Robyn Raya’s field project centered on hydrology, the study of water movement, which is one of Ketchen’s career interests.

“On another field trip with Dr. Black, a hydrology expert told us if you fix the water, you’ll fix everything else,” said Ketchen. That resonated with him. At the center, his team tested water samples and took temperatures at different locations, learning that the tributary waters were warmer than the water in the main river. That was a surprising discovery because it’s typically the opposite in the Yakima Valley.

MAKING CULTURAL CONNECTIONS WITH LOCAL TRIBE

MAKING CULTURAL CONNECTIONS WITH LOCAL TRIBE

This trip was about more than science, however. It was also about connections with other Native Americans across the country and globally. The teams took a day off from their research to meet members of a Panamanian indigenous tribe called the Boruca. The tribal elders shared about family life, traditions, and gave a demonstration in purse making, in which they grow and weave the cotton and use leaves to create different dye colors. Students also painted traditional masks, used to warn potential conquerors away, and they participated in their tribal dances.

“We learned that the tribal members in Costa Rica are experiencing many of the same issues as the Native American tribes,” said Black, who pointed to their concerns about water usage and land sovereignty.

“It was cool to see how much respect they have for the land,” said Stewart. “And how self-sufficient they are.”

Ketchen particularly valued the time spent networking with other Native American students, mentors and even visitors to the center.

“Well, I really liked the whole trip, but meeting other people was what I liked best,” said Ketchen. “While we were in the field, we ran into a family from France bird watching on the grounds. I don’t think they had ever met a Native American before, and they were excited … It was nice.”

He also found it surprising that the other Native American students on the trip, including his lab partner who was from Montana, had tastes and stories that were so similar to his own even though they lived in different places.

“For me, it was great to get a different type of education – to meet other people who are culturally like me – while getting an education,” concluded Ketchen.

Pictures courtesy of Brian Amdur Photography

After years of sacrifice, of late night study sessions and countless hours spent in the library and computer labs, Heritage graduates celebrated earning their degree at the 2018 Commencement in May.

After years of sacrifice, of late night study sessions and countless hours spent in the library and computer labs, Heritage graduates celebrated earning their degree at the 2018 Commencement in May. The Violet Lumley Rau Outstanding Alumni Award was given to Colleen Sheahan for her work establishing and running a private Christian school in Yakima. Fifteen graduates received the Board of Directors Academic Excellence Award, which is given to undergraduates who completed their degree with a perfect 4.0-grade point average. This year’s recipients were: Aryell Adams,Social Work; Kayli Berk, English/Language Arts; Aimee Bloom, Education; Meagan Gullum, Social Work; Tifanny Macias, Education; Daniela Medina, Education; Itzamary Montalvo, Education; Debra Olson, Education; Alexandra Orozco, Social Work; Perla Perez, Social Work; Karima Ramadan, Early Childhood Studies; Filipp Shelestovxskiy, Education; Jessie Shinn, Accounting; Ana Tapia, Social Work; and Ashley Zahn, Education. The President’s Student Award of Distinction, which is given to an undergraduate with a distinguished record of academic excellence and service to the university, was given to Aleesa Bryant, Biomedical Science.

The Violet Lumley Rau Outstanding Alumni Award was given to Colleen Sheahan for her work establishing and running a private Christian school in Yakima. Fifteen graduates received the Board of Directors Academic Excellence Award, which is given to undergraduates who completed their degree with a perfect 4.0-grade point average. This year’s recipients were: Aryell Adams,Social Work; Kayli Berk, English/Language Arts; Aimee Bloom, Education; Meagan Gullum, Social Work; Tifanny Macias, Education; Daniela Medina, Education; Itzamary Montalvo, Education; Debra Olson, Education; Alexandra Orozco, Social Work; Perla Perez, Social Work; Karima Ramadan, Early Childhood Studies; Filipp Shelestovxskiy, Education; Jessie Shinn, Accounting; Ana Tapia, Social Work; and Ashley Zahn, Education. The President’s Student Award of Distinction, which is given to an undergraduate with a distinguished record of academic excellence and service to the university, was given to Aleesa Bryant, Biomedical Science.

A whirlwind of events in March brought together a campus and a community to celebrate the

A whirlwind of events in March brought together a campus and a community to celebrate the

In the evening, Heritage hosted the President’s Inauguration Jubilee at the Yakima Seasons Performance Hall. It was an arts and cultural event that celebrated the richness of the Yakima Valley and the people who call this area home. This multicultural repertoire of music, poetry,

In the evening, Heritage hosted the President’s Inauguration Jubilee at the Yakima Seasons Performance Hall. It was an arts and cultural event that celebrated the richness of the Yakima Valley and the people who call this area home. This multicultural repertoire of music, poetry, the Yakima Symphony Chorus, traditional Native American dancing by The Four Seasons Travelers, pop and rock music by the Latino band Avión, and contemporary indie music by Naomi Wachira.

the Yakima Symphony Chorus, traditional Native American dancing by The Four Seasons Travelers, pop and rock music by the Latino band Avión, and contemporary indie music by Naomi Wachira. The celebrations capped off with the formal installation during a ceremony steeped in academic tradition. The event began with the grand procession of regalia-clad faculty, visiting dignitaries from other colleges and universities, members of the platform party, student representatives, and the Yakama Warriors color guard marching across campus from the Kathleen Ross snjm Center to Smith Family Hall in the Arts and Sciences Center. They marched down the aisle to a recording of the “Heritage University Tribute Anthem,” composed for the university by Joan McCusker, IHM and performed by the Yakima Symphony Orchestra. Davis Washines, chair of the Yakama General Council and Dr. Kathleen Ross, snjm each presented an invocation and Dr. Keith Watson, president of Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences, and Norm Johnson, WashingtonState Representative, 14th District (R) presented greetings.

The celebrations capped off with the formal installation during a ceremony steeped in academic tradition. The event began with the grand procession of regalia-clad faculty, visiting dignitaries from other colleges and universities, members of the platform party, student representatives, and the Yakama Warriors color guard marching across campus from the Kathleen Ross snjm Center to Smith Family Hall in the Arts and Sciences Center. They marched down the aisle to a recording of the “Heritage University Tribute Anthem,” composed for the university by Joan McCusker, IHM and performed by the Yakima Symphony Orchestra. Davis Washines, chair of the Yakama General Council and Dr. Kathleen Ross, snjm each presented an invocation and Dr. Keith Watson, president of Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences, and Norm Johnson, WashingtonState Representative, 14th District (R) presented greetings.  Before representatives from the Student Government Association, Faculty Senate, Staff Educators Senate, and university alumni make their remarks, students from the Wapato High School Choir “En Vox” performed an interlude of choral music. They later sang the university’s alma mater Lift High the Banner! , written by Dr. Curtis L. Guaglianone and arranged by Aaron L. Jameson. David Cordova, friend and former colleague of Dr. Sund, made the introduction before Heritage Board of Directors Chair Pat Oshie presented Dr. Sund with the chain of office during the Ceremony of Investiture.

Before representatives from the Student Government Association, Faculty Senate, Staff Educators Senate, and university alumni make their remarks, students from the Wapato High School Choir “En Vox” performed an interlude of choral music. They later sang the university’s alma mater Lift High the Banner! , written by Dr. Curtis L. Guaglianone and arranged by Aaron L. Jameson. David Cordova, friend and former colleague of Dr. Sund, made the introduction before Heritage Board of Directors Chair Pat Oshie presented Dr. Sund with the chain of office during the Ceremony of Investiture. Steve Dupuis, the IMSI director at Salish Kootenai College in Pueblo, Montana, reached out to Dr. Jessica Black about the trip, which he had done the year before. It was structured to bring tribal students in the sciences together from colleges across the country. Heritage University’s participation was made possible by a partnership with the All Nations Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation program, in conjunction with the Organization for Tropical Studies.

Steve Dupuis, the IMSI director at Salish Kootenai College in Pueblo, Montana, reached out to Dr. Jessica Black about the trip, which he had done the year before. It was structured to bring tribal students in the sciences together from colleges across the country. Heritage University’s participation was made possible by a partnership with the All Nations Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation program, in conjunction with the Organization for Tropical Studies. Kimberly Stewart and Zane Ketchen were two of the students invited to travel to the Central American country. When Stewart received the text from Black, she was immediately intrigued – not just about the chance to dig into field work in such a rich environmental location but also because she would meet and work with other Native American students from around the country. “I had traveled, but never to Central America,” said Stewart, a junior who is interested in working with the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources when she graduates. After an 11-hour flight to San Jose, the team hopped aboard a bus for the six-hour journey into the Talamanca Mountains the next day. Taking the coastal route, Ketchen had his first look at Costa Rican wildlife, including crocodiles, macaws, and Black’s favorite, the toucan!

Kimberly Stewart and Zane Ketchen were two of the students invited to travel to the Central American country. When Stewart received the text from Black, she was immediately intrigued – not just about the chance to dig into field work in such a rich environmental location but also because she would meet and work with other Native American students from around the country. “I had traveled, but never to Central America,” said Stewart, a junior who is interested in working with the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources when she graduates. After an 11-hour flight to San Jose, the team hopped aboard a bus for the six-hour journey into the Talamanca Mountains the next day. Taking the coastal route, Ketchen had his first look at Costa Rican wildlife, including crocodiles, macaws, and Black’s favorite, the toucan! FIELD WORK GIVES STUDENTS HANDS-ON RESEARCH SKILLS

FIELD WORK GIVES STUDENTS HANDS-ON RESEARCH SKILLS MAKING CULTURAL CONNECTIONS WITH LOCAL TRIBE

MAKING CULTURAL CONNECTIONS WITH LOCAL TRIBE