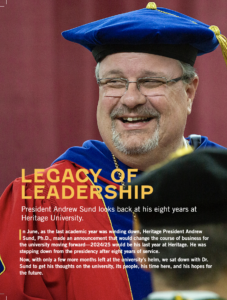

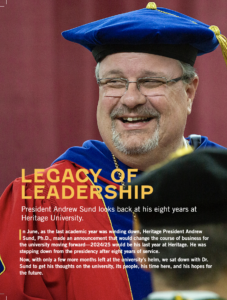

Heritage University President Dr. Andrew Sund

Dr. Sund, it’s been eight years since you accepted the position of Heritage University president. What made you decide to do so?

I had known of Heritage because I’d met both my predecessors in a variety of settings. I came from a university in Chicago with a primarily Latino community, and I knew the two institutions shared some similarities, primarily in their focus on marginalized communities. That resonated with me and continues to resonate with me. So, I often thought that Heritage was an institution I would love to work at. When the position opened up, I decided to apply.

What did you feel was special about Heritage?

The university’s mission to serve underserved populations, particularly the Native American community and Heritage’s location on the Yakama Nation. I thought I could contribute to the mission and grow as a person and as a professional. Also, being in a rural community seemed quite unique and inviting to me.

What growth opportunities did you see for Heritage?

I saw opportunities to grow enrollment by focusing more strongly on Heritage’s original mission. Previously, there was an effort to bring in other populations that weren’t part of the original mission of serving the people of the Yakima Valley. I felt that by focusing strongly on the mission and providing the proper services to students, we could grow those student numbers. The groundwork had been laid that we could take to the next level. Heritage’s focus must always be on serving people who are first-generation college students, who come from low-income backgrounds, face cultural obstacles, and who need financial support to achieve their goals. It’s a unique mission, and Heritage says, ‘This is who we are. We exist to serve this population.’ Whether that’s helping a student with a flat tire, providing some emergency funding for gas, or having a food pantry that allows students the ability to take food home – at Heritage, students are never a number. Students and faculty work together for students’ well-being. They share their cell numbers and text each other anytime, day or night, for academic or other reasons. It’s rare, really special, and it’s all part of our focus. I often say Heritage is what higher education should look like everywhere. We should be the norm, not the exception. Higher education was created in Europe back in the Middle Ages to serve elites – we challenge that, and we are willing to change processes, systems, anything we can so that students can have access and success but never compromise the quality of education.

What goals have been accomplished in your eight years?

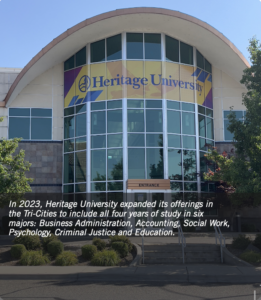

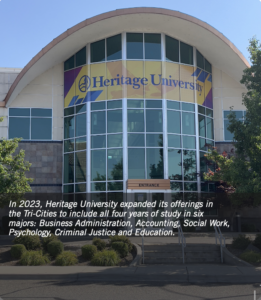

Heritage University Tri-Cities in Kennewick, Wash.

Well, we’ve developed a closer relationship with the Yakama Nation, something I’m very proud of. It’s important because it’s the root of the institution. We were founded to ensure access to higher education for the people of the Yakama Nation, to meet them where they are, and to bring them to the level they want and need. So, the first accomplishment is that we are proud of our mission and who we serve, and it’s important that we never question that.

From that, we’ve grown Native enrollment from eight percent to 14 percent. Doubling our number of Native American students during my time here is a major achievement. Tribal council members have commented many times on how closely I’ve worked with them, and that’s a major source of pride and accomplishment for me.

What are the specific programs you’ve been part of realizing?

There are new majors we’ve brought to the University, like the Master of Social Work and the Master of Mental Health Counseling. Those address the actual needs of people in the Valley, so that’s significant. Of course, we expanded Heritage’s reach a couple of years ago through our new Tri-Cities location. It’s a work in progress that’s hopefully going to bring great results for many years to come.

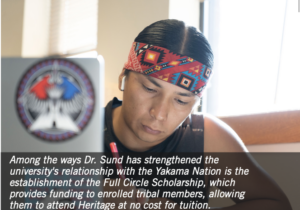

The Heritage University Yakama Nation Full Circle Scholarship is another meaningful program because it makes it possible for qualifying students to earntheir undergraduate degree with no out-of-pocket tuition costs. It’s unique in that it covers tuition that remains after other scholarships and grants, and it’s renewable for up to six years.

The Ross Institute for Student Success will help establish the University as a center for teaching methodologies for first-generation college students, which is our expertise. This really formalizes it in an entirely new and significant way.

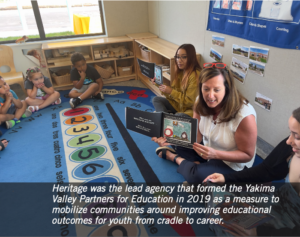

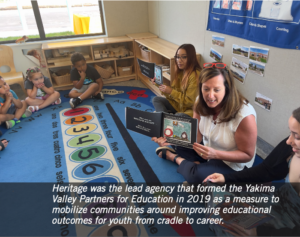

And finally, Yakima Valley Partners for Education (YVPE) was one of the first initiatives I was part of establishing at the University. YVPE lets Heritage be part of a collaboration with schools and communities to improve educational outcomes for all youth, cradle to career.

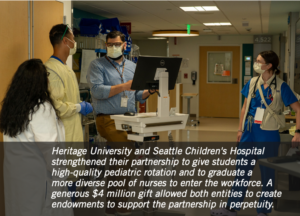

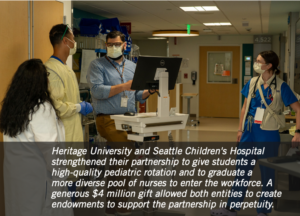

Heritage University and Seattle Children’s Hospital

strengthened their partnership to give students a

high-quality pediatric rotation and to graduate a

more diverse pool of nurses to enter the workforce. A

generous $4 million gift allowed both entities to create

endowments to support the partnership in perpetuity.

How do you think faculty have developed during your tenure?

I’m very happy with how we’ve been able to maintain and grow the quality of faculty at Heritage University. We’ve had people join our institution with PhDs from the most prestigious institutions in the Pacific Northwest and the nation, including two professors who were undergraduates at HU, went off to earn their PhDs, and are now back at HU as professors.

Any unexpected bumps in the road?

The pandemic, of course. I was so proud of everyone who worked together to manage the effects of the pandemic on our students. We don’t have the resources of larger universities. Yet, we pivoted, and it was the great work of many people, especially in the IT department, who had to make sure everything happened. Faculty and staff worked very hard to make sure students could continue, and students managed to do it despite many difficulties in their personal lives.

Eight years since you came to Heritage, how is the university doing financially?

Perhaps one of the accomplishments I might be remembered for most is that we basically doubled our endowment in my time here. Fundraising has been a major success and as I said, it’s not something I take credit for fully because fundraising is the result of years of work and making sure you’re telling the Heritage story, sharing the mission, and developing connections with people who can support that mission. I did some of that, but I also continued relationships that were built by my predecessors and others, so I am very grateful for them and very happy I was able to continue with that. We received some very big gifts recently – a six million dollar gift and the latest one $10 million. It’s remarkable for a small institution like Heritage that we have that level of support.

Widening the lens, what challenges does higher education face today?

Founding HU president Dr. Kathleen Ross stands with HU President Dr. Andrew Sund

We’re facing a crisis of ‘value.’ It used to be understood you’re paying for something that’s going to bring you future rewards. That does not exist as it had. Many people are questioning whether it’s worth the ‘sticker price’ to earn a degree – though it’s always funny to me that many critics of higher education want their own kids to go to college.

But, as a sector, the cost of higher education is way too high, making it very difficult for people to attend if they don’t have the resources. Pell grants have not grown the way they should. State support hasn’t kept up. There’s inflation. We need to continue fundraising to make up those differences. And we must always demonstrate our value proposition – in other words, what you get out of a Heritage University education. Heritage was the lead agency that formed the Yakima Valley Partners for Education in 2019 as a measure to mobilize communities around improving educational outcomes for youth from cradle to career.

The cost challenges are what’s made me lose sleep. Yet at Heritage, we have worked to keep tuition significantly lower. We’ve been successful where many small institutions have closed in the past few years due to the high cost of keeping the infrastructure going while at the same time experiencing lower enrollments.

What inspires you about Heritage students?

I think about how, in the wintertime especially, I see students coming in when it gets dark early, probably after having worked an eight-hour shift somewhere. They’re devoting their time trying to further their lives through education, which, of course, is the most powerful tool to overcome obstacles in life — and that is inspiring to me. It’s their determination despite difficulties they may be facing in their personal lives. Anytime I’m having a hard day, I just need to look at our students and how hard they work.

Children playing in the new Early Learning Center at Heritage University

What inspires you about Heritage faculty?

Our faculty are here because they want to be part of this; they’re committed to our students’ success, and they’re willing to work with all sorts of innovative teaching practices and the sort of close- touch contact that we were talking about earlier. They could be elsewhere, but they’re here because they believe in the mission and our students.

Who else inspires you?

Those who share their time, their expertise, their monetary support, which is so important to Heritage. I’ve always been so impressed with the commitment of the community towards Heritage, whether it’s through board service, or volunteering in other ways, or through their financial resources. It really shows several things – that people in the Yakima Valley and in the Seattle area truly understand there’s a question of equity here. They know that providing opportunities is a fairness issue.

Heritage was the lead agency that formed the Yakima Valley Partners for Education in 2019 as a measure to mobilize communities around improving educational outcomes for youth from cradle to career.

Further, there’s a tremendous understanding that, beyond equity, this makes sense for the Yakima Valley. Our students – the Latino population, the Native American population – they’re becoming the majority in the Valley. They’re going to hold the future jobs. We need professionals. We need people to be in education, business and the public sector. So, there is a great understanding also of the economic impact that Heritage has on the Yakima Valley. It’s a very thoughtful group and one that has tremendous pride in Central Washington and understands the great privilege of having a university for this community right here in the middle of the hop fields.

What are your continuing hopes for Heritage University?

To continue to develop master’s degrees that are needed in the community. That could be very powerful for the institution. And more research opportunities, showing what we do at Heritage that brings scholars from other areas so they can learn from us, and we can learn from them.

What’s next for you, Dr. Sund?

It’s a fluid situation, but I’m looking forward to flexibility in my work life, perhaps as a consultant, and to work in my areas of expertise. So guiding leadership or in accreditation, in work that revolves around helping students who have had limited access to higher education. I want to keep using the skills and knowledge I’ve developed. I’m looking forward to having flexibility so I can travel. I would like to be – what do you call it? – a snowbird because I have a home in Chicago where my sons are, but when it’s February in Chicago, I want to go back to Chile.

A partnership project designed to boost the number of people of color serving as lawyers in Central Washington kicked off in 2022. The Law School Admission Council Prelaw Undergraduate Scholars Program partnered Heritage University with the law schools at Seattle University, University of Washington and Gonzaga University.

What will you miss about living here?

I will miss the people. I will miss many colleagues who I’m very happy to consider my friends, and now stronger friends in some ways because I’m not going to be their boss anymore. I will miss Tim’s cooking in the cafeteria. I’ve really enjoyed the weather here — it’s so pleasant for so many months. So I’ll miss driving through the hop fields and the beautiful scent in the air at different times of the year, the apples, the mint. I’ve so enjoyed early morning walks at Cowiche Canyon, when it’s quiet and still with the breeze and the peace and quiet all around you.

Among the ways Dr. Sund has strengthened the

university’s relationship with the Yakama Nation is the establishment of the Full Circle Scholarship, which provides funding to enrolled tribal members, allowing them to attend Heritage at no cost for tuition.

I love the relaxed lifestyle in the Valley and the wonderful social and dining scene of the restaurants and wineries. Yakima, where I live, has this sort of small-town feel even though it’s not such a small town: the civic clubs and the involvement from so many people here who are so civic-minded. You get to meet people here, and that’s what I’ve really enjoyed.

![]()