Alumni Spotlight: Leveling the Educational Playing Field

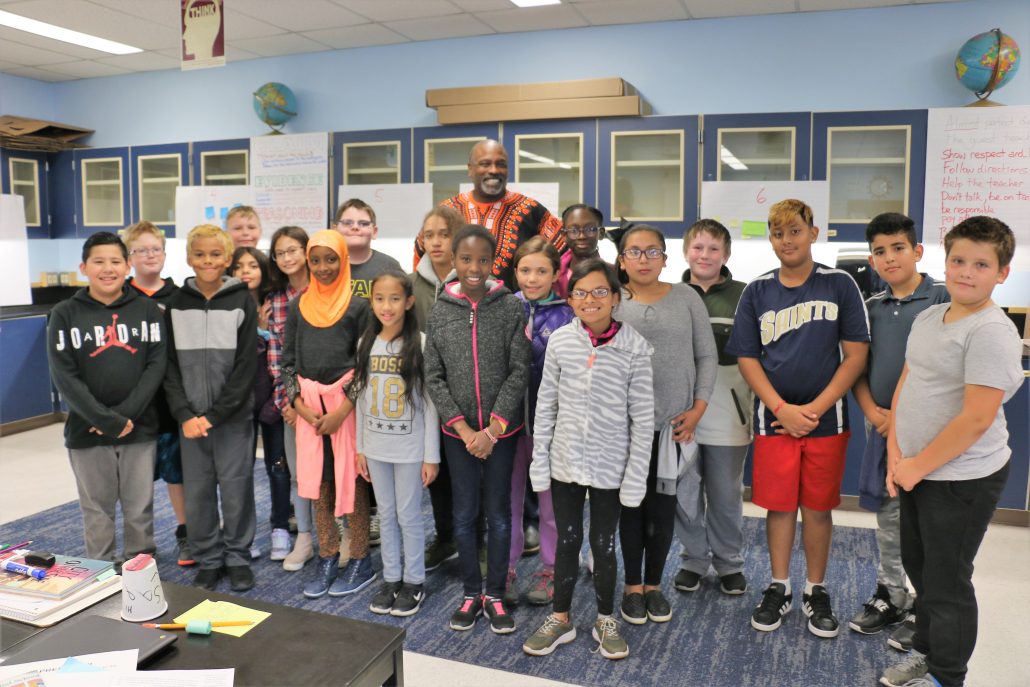

Glenn Jenkins with his class of fifth-graders at Dick Scobee Elementary School in Auburn, Washington. In his class of 23 students, there are eight different cultures represented.

Students win with the academic approach that weaves culture and racial equity into the classroom.

Glenn Jenkins’ first brush with higher education started very early. He attended college at the age of eight!

Yes, he was extremely bright, but this Heritage alumnus was actually tagging along with his mom as she took courses towards her bachelor’s degree in interior design. Jenkins laughs boisterously as he recalls the day he made his presence well known to a professor, by raising his hand with the correct answer to a question thrown out to students in his mom’s college-level English class.

“After that, I did all of my mom’s English homework,” chuckles Jenkins conspiratorially, admitting he also became the family’s go-to handyman after mom learned she could throw him a DIY book, and he would teach himself how to wire electrical outlets and clear drains.

Education was seemingly infused into Jenkins’ DNA at birth. His passion for education as an equalizer for children of color led him to become an elementary school teacher in the Auburn School District in western Washington state. He was also elected a year ago to the board of the Washington Education Association Representative Assembly (WEARA) in the role of Equity-At-Large Board Director. Over the past year, Jenkins has become the implicit bias trainer, conducting professional development in the areas of race, gender and disability, believing that until educators themselves are exposed to racial equality in education they can’t nurture it in their classrooms.

RACISM LED HIM TO THE CLASSROOM TO ADVOCATE FOR EQUITY

Born in Detroit, Michigan, Jenkins attended a rigorous STEM-focused magnet high school, Cass Technical High School, which counts songstress Diana Ross, comedian and actress Lily Tomlin, and automaker and manufacturer of the time-traveling car in the Back to the Future movies, John DeLorean, as former students. He jokes that he and his friends were “nerds, but cool nerds,” taking tough classes like chemistry, biology and engineering while maintaining the mandatory 3.0-grade-point average.

He was working as a freelance writer for the Michigan Citizen newspaper in 1996 after graduation when he decided he wanted to try somewhere new.

With no destination in mind, he opened an atlas, closed his eyes, and pointed. His finger landed on Tacoma, Washington. Within three months, he moved cross- country and was working in the Pacific Northwest.

“I’ve had about 37 jobs in my lifetime,” said Jenkins. “I write them on the board for the kids every year to show them that success is not a straight line.”

New telecommunications companies were opening their doors almost daily then, and he worked for a number of them in various engineering roles. He eventually joined one that was building out the fiber network in Seattle.

“I became known as the go-to guy,” he said.

One time, his boss called him at five in the morning and said the entire state of Alaska was down, and he had six hours to fix it. And he did! However, when he was passed over for a promotion solely because some of his coworkers were uncomfortable with his skin color, Jenkins decided it was time for a change. That overt racism drove him into education.

He stumbled upon the teaching program at Heritage accidentally, after finishing his associate degree at South Seattle Community College. At the time, the university operated a satellite teacher preparation bachelor’s degree program at the community college.

“The social justice framework of Heritage was exactly what I was looking for if I was going to be a teacher,” said Jenkins, who graduated from Heritage in 2011 with a bachelor’s degree in education and an English as a Second Language endorsement. “Their openness to cultural representation was really important to me.”

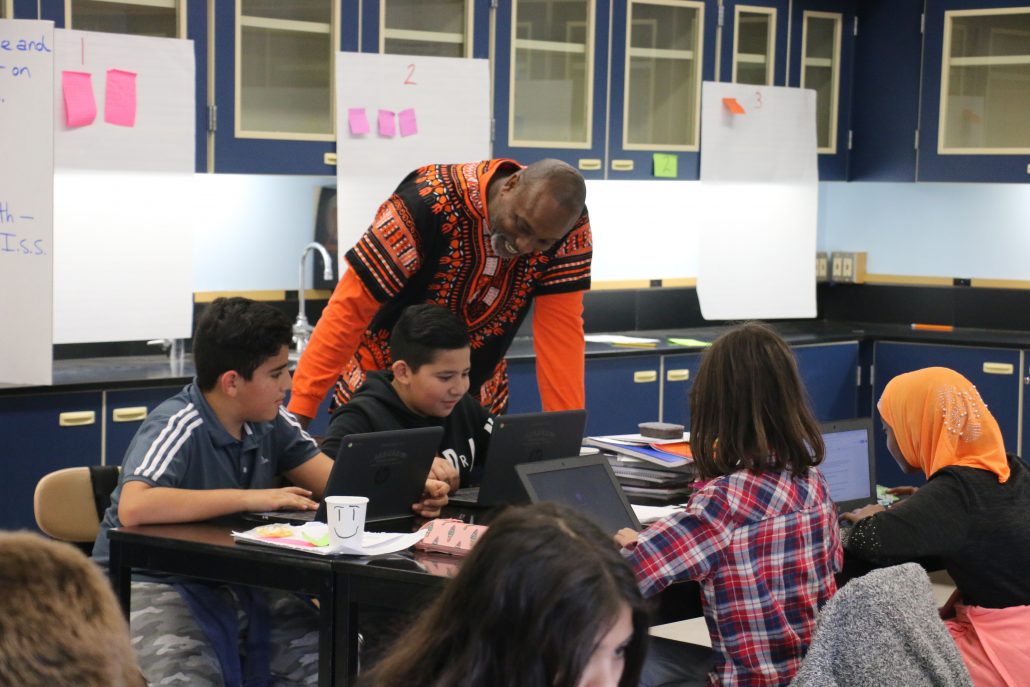

Jenkins assists students Angel Cabral, Gabriel Hernandez-Garza, Feisa Hussein and Jasmine Perry as they work on the math assignment, a house building project.

WHEN STUDENTS GET COMFORTABLE, THEY BECOME ENGAGED

Jenkins runs a tough classroom, but the kids see he cares. He makes a point of being inclusive and curious about their cultures. He shared his own ethnicity in cultural nights at school and encourages his students to share theirs. He asks for help with his Spanish and works hard to get the pronunciation of every child’s name exactly right because he sees that as a sign of respect.

Njeri Bañuelos was a student of Jenkins when he was teaching fourth, fifth and sixth grades in a split classroom. She struggled with English and other coursework, particularly math. Jenkins saw that, and knew instinctively that he had to draw her out to break down the barriers to her learning.

“I was terrible at math,” said Njeri, now an eighth-grader. “I didn’t want to be there, but Mr. Jenkins pushed me to get better. I would be mad at myself and frustrated, but I didn’t want to ask questions. He told me not to be embarrassed because no one ever stops learning. It’s true!”

Njeri’s mom, Guadeloupe, explained that her daughter practically brought Mr. Jenkins home every day – by talking about him so often to the family. Njeri would quote facts about topics like space junk, and after a while, her brothers would simply say, “Let me guess, Mr. Jenkins?”

“My whole classroom is based on the fact that I know you don’t know,” he explained. “But you have to feel comfortable enough in order to ask questions. The best way to make you feel comfortable is to be sure the math, science, history and reading lessons have someone in it that mirrors who you are.”

He gives an example of a long-standing math scavenger hunt in which the clues were always white mathematicians, even though the classroom was comprised of 80% children of color.

“I turned the scavenger hunt into a cultural scavenger hunt that had mathematics tied to it,” he said.

He changed the clues to mathematicians from the countries his students came from, and with 18 different nationalities, including the Marshall Islands and Guam, it wasn’t easy! Students were tasked with learning more about their person, and connecting with that shared background. Now there was excitement! Today, the entire district has adopted his scavenger hunt.

“I’m really happy to be in the district I’m in, they are as culturally responsive as they can possibly be,” said Jenkins.

Another example is the impact he had on the district’s teaching of the Oregon Trail. Most history books leave out the heroics of York, an African slave who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their expedition and who saved the men hundreds of times.

Jenkins said he asks people to tell him who was on the trip, and the most common responses are Sacagawea and the dog. Most don’t know anything about York because he wasn’t written about. Once the district heard Jenkins speak about this, it purchased the book, York, by Brad Phillips, and made it mandatory reading for fourth graders.

“Elementary-aged kids get it,” said Jenkins. “They don’t want to treat people badly, especially when it comes to race.”

LEADING THE PUSH FOR CULTURAL AND RACIAL EQUITY TRAINING FOR EDUCATORS

Adults are more of a challenge, however. In addition to his position on the board of the Representative Assembly, he’s on a state work team for the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) working on phase-ins of additional components to the state’s curriculum. The state recently added an ethnic studies elective to middle and high school, but Jenkins would like to see it start in pre-k and be a required part of the coursework. He would also like ethnic studies mandatory for state educators.

Adults are more of a challenge, however. In addition to his position on the board of the Representative Assembly, he’s on a state work team for the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) working on phase-ins of additional components to the state’s curriculum. The state recently added an ethnic studies elective to middle and high school, but Jenkins would like to see it start in pre-k and be a required part of the coursework. He would also like ethnic studies mandatory for state educators.

“With optional training, you get people who really want to take it, not the people who need to be in the room,” he said. “If we get the people who have not been in the room in the room, they will see.”

Jenkins believes the push for equity is actually a push for excellence because data shows if students and their ethnicity are treated with respect, the opportunity gap closes. Njeri would agree with that. She was recently invited to be a leader student in the school, mentoring sixth graders.

“Mr. Jenkins changed me in a good way,“ said Njeri. “He inspired me to advocate for myself. I still talk about him to my friends, and they all say they wish they had him too.”

This impact, on kids of color in his classroom, is what he’s most proud of in his diverse and powerful body of work.

“Students who are now in high school come back and tell me they are taking physics or AP math,” said Jenkins. “They realized in my classroom, knowledge was the equalizer. It’s something no one can ever take from you.” .