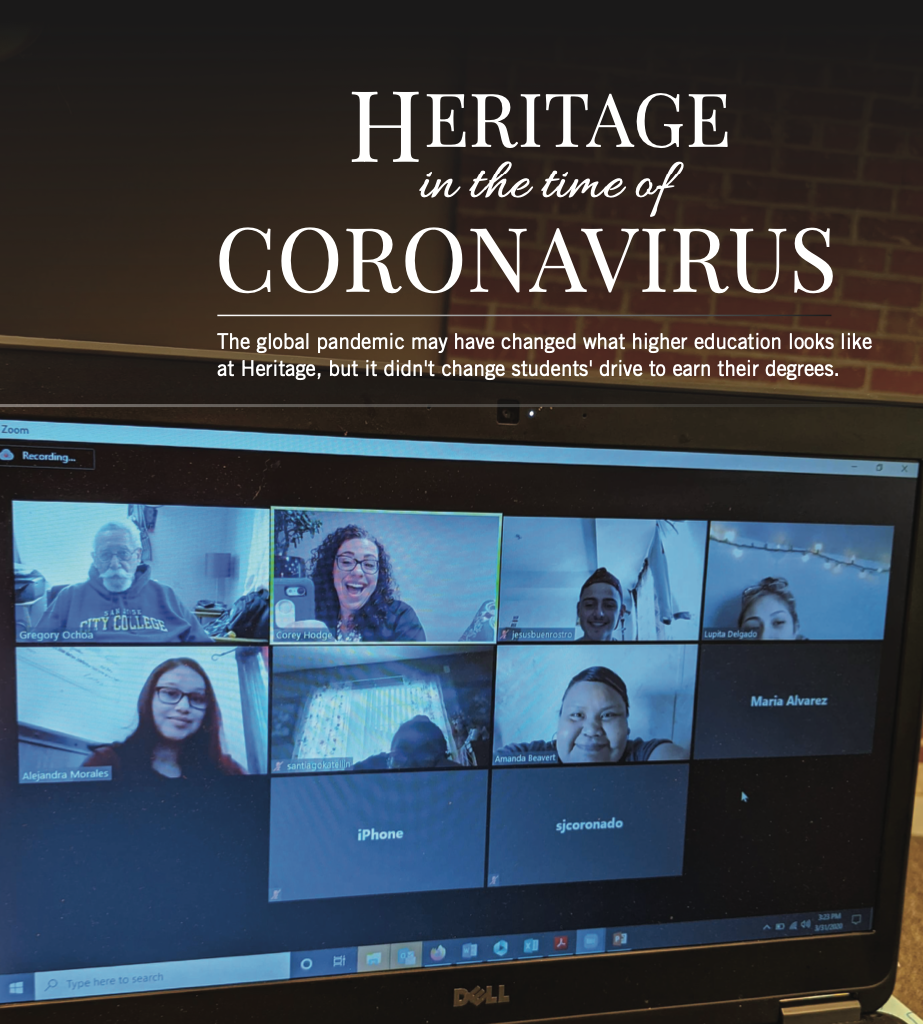

Heritage in the time of Coronavirus

Dining rooms and bedrooms become classrooms as COVID-19 forces Heritage to take student learning online through Zoom. Here, Professor Corey Hodge leads one of her social work classes.

Dr. Melissa Hill, vice president orders limiting gatherings of more that all non-essential businesses for student services, vividly recalls the days leading up to the closure of Heritage University’s campus in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. On February 27, she and her fellow vice presidents and President Andrew Sund were traveling to Seattle for a leadership conference. Just two days prior, Seattle and King County officials confirmed the first United States COVID-19-related death of a patient in a nursing facility. By the time the team returned to campus a few days later, the number of cases had climbed to 14, and deaths associated with the disease had increased to six. News reports were filled with stories of concerned citizens calling for the closure of Seattle-area businesses, schools and universities.

“We realized that we were entering into an unprecedented time and that we needed to move rapidly to build our plan of action,” said Hill.

The university’s leadership team started meeting daily to prepare a contingency plan in case they had to close the campus. As they worked to figure out how to minimize the impact on students’ education, the rate of infection in western Washington state continued to climb. On Friday, March 6, three Puget Sound area colleges announced they were closing their campuses and moving instruction online, just as Heritage students were wrapping up their midterms and heading off to spring break. By the following Wednesday, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic, and Washington’s governor made his first orders limiting gatherings of more than 200 people.

“We were watching things escalate pretty rapidly in western Washington,” said Hill. “As the number of cases climbed higher and higher in the Seattle area, we seemed pretty isolated here in the Yakima Valley. Still, we knew it was just a matter of time before it would come across the Cascades and into our community.”

By the end of spring break, it was clear that the university had to move instruction online, at least for the short term. Sund announced on Friday, March 13, that spring break was extended by one week to give faculty and students time to prepare to move to small group meetings, where social distancing could be observed, and remote learning. The plan was to resume the semester on Monday, March 23, with campus offices open and staff in place, but almost all instruction online for the next two weeks. However, on the day classes were slated to begin, the governor issued an executive order that all non-essential businesses were to close their physical spaces, and workers were to stay home. By 11:00 that morning, everyone was sent home, the campus was shut down, and all classes and business functions were moved online.

“One of the things that we did well was responding rapidly when it became clear that we were going to have to dramatically change the way we do business,” said Sund. “Things were shifting daily, sometimes hourly, and we needed to be flexible. We had to ensure the health and safety of our students, faculty and staff, and we needed to build ways that everyone could remain safe and complete their education.”

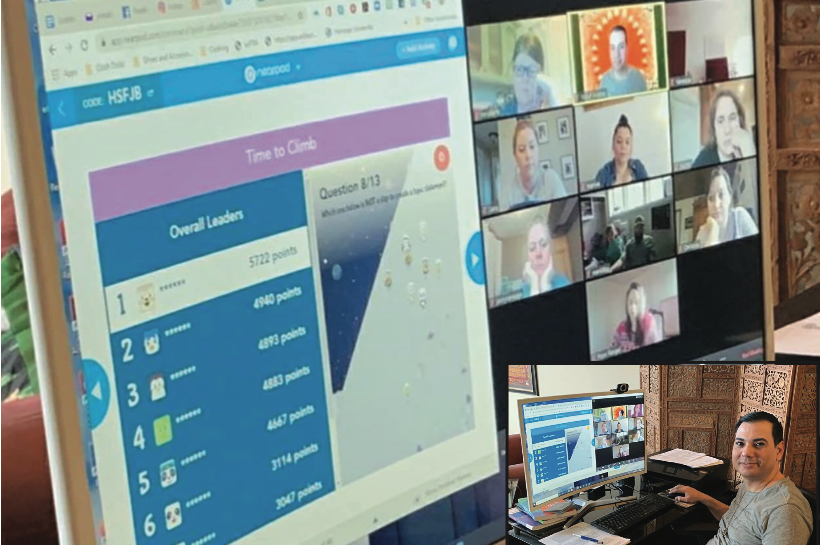

Miles apart but still close together, Heritage’s various departments continue to operate through virtual meetings.

MOVING INTO THE VIRTUAL WORLD

Moving from traditional classrooms to remote learning took a team of individuals with varying specialties. Luckily, much of the infrastructure was in place for distance learning and telecommuting. The university’s Information Technology (IT) department rebuilt its infrastructure following the 2013 fire that destroyed Petrie Hall. The new system contained redundancies to protect critical data from future catastrophes. A by-product of this precaution is that there is more than enough space available to handle the demands of an entire campus working remotely.

Remote learning and telecommuting had been in existence on some level for years at Heritage. Many faculty and staff could already access their desktop computers remotely. MyHeritage, the university’s academic platform, was in place and used to varying levels of its full capacity by faculty and students. Much of the work preparing for the campus closure was training those who were not already familiar with remote access and assisting full time and adjunct faculty who were not fully utilizing MyHeritage with moving their entire curriculum onto the platform. While the university’s Center for Intercultural Learning & Teaching provided MyHeritage training and support, IT secured Zoom accounts for all faculty, staff and students to use for meetings, team projects and group study, and virtual classrooms.

Dr. Yusuf Incetas – photo right – and his ED 496 Senior Capstone students meet virtually online through Zoom.

“By far, our biggest challenge was ensuring that everyone had access to computers and Wi-Fi from off-campus,” said Aaron Krantz, director of IT. “We distributed every laptop we had at our disposal, and we’re purchasing additional laptops for distribution when fall semester opens.”

Aside from the academic challenges, Heritage had to build its strategies surrounding student services. Even during normal times, the demand for student services such as the Academic Skills Center (ASC) and tutoring, CAMP and TRIO, and the HU Cares program is high.

“Many of our students need these extra supports to succeed in college. Tutoring is critical and our ASC moved rapidly to open virtual face-to-face tutoring,” said Hill. “As the semester progressed with virtual classrooms, we received an increasing number of referrals to HU Cares (a safety-net program that assists students in crisis with extra support such as emergency funding, mental health counseling, food and transportation assistance.)”

Hill explained that the issues students faced varied from food insecurity to greater need for assistance with mental health issues, to struggling with being able to work well in the new environment.

“A major challenge for our students is identifying a safe and quiet place to study,” said Hill. “Not only were they at home trying to stay connected and learn, many of our students have school-aged children or younger siblings who were also home needing to access computers and study areas to do their work. When we would ask students, ‘where is your quiet space to do your work?’ we were frequently told, ‘I don’t have one.’ It’s a real challenge when you share a small space with your active family, juggling everyone’s needs.

“On top of that, we have a higher number of students who share their homes with essential workers, particularly in agriculture. This is an area that is being particularly hard- hit by the pandemic. We saw an increase in mental health issues such as stress, depression and anxiety as students dealt with these pressures.”

Heritage addressed these needs through a variety of means. The university contracted with a licensed therapist to provide additional mental health services through remote access. Funds received from the government’s CARES Act Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund helped address food insecurity. Every Heritage student received $500 to assist with financial hardships brought on by the pandemic. The money came from a combination of private contributions to the university’s Emergency Fund and funding received from the federal government’s CARES Act Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund. DACA students, who were explicitly excluded from receiving assistance through the CARES act, were provided assistance through giving by several private donors who wanted to ensure they had the same level of support as non-DACA students.

Throughout it all, communication was, and remains, key throughout the shutdown. Heritage hosted several live Zoom information sessions in both English and Spanish. Some were specific to university operations and academic delivery during the shutdown. Others focused on the virus and safety precautions everyone can take to limit its spread.

Enzo Eagle helps Heritage Admissions distribute new student welcome packets during a drive up session at the university.

RECRUITING FOR THE CLASS OF 2024

It isn’t just the current class of Heritage students impacted by the pandemic. At the time of the campus closure, admissions counselors were hard at work bringing in the upcoming class of Heritage Eagles. While many universities’ application and acceptance periods were passed, Heritage maintains open admissions. Students can and do, apply for admission throughout the year, sometimes as close as a few days before the start of the semester.

The months before high school graduations tend to be among the busiest for Heritage recruiters as they help incoming students complete their application requirements and reach out to other prospective students who are just beginning to consider their options.

The order to close campus meant admissions counselors could no longer meet prospective students in person, on campus. However, it didn’t mean the face-to-face meetings stopped. Counselors and student ambassadors moved their work into their home offices, meeting with future Eagles virtually through Zoom.

Additionally, the university modified some admissions requirements to remove barriers that could keep students from enrolling. For example, the university changed the requirement for official transcripts. The closure of school districts made it difficult for students to access official transcripts. However, they do have access to an online grade book that shows the courses taken and the grades received throughout their high school career. Heritage is now using these in place of the transcripts until official transcripts can be acquired. Additionally, the requirement for placement testing to determine students’ level of college readiness is waived. Instead, placement for math and English are being determined through SAT or ACT scores, when available, or through documents being used as transcripts.

Incoming students like Viviana Phillips, from A.C. Davis High Schoo, took advantage of Admissions’ drive-up pick-up option to receive their new student welcome packets over the summer.

“The burden of these times shouldn’t be placed on these students’ shoulders,” said Gabriel Piñon, director of Admissions. “Heritage University is all about access and equity. We are going to do everything we can to ensure that those who want to earn a college degree can do so.”

Where things got a little tricky for Admissions was the public celebrations of full-ride scholarship recipients that’s become a tradition for the university.

Each year in the early spring, Heritage makes surprise visits to the homes and schools of the winners of its full-ride scholarships to announce their award. Each recipient is celebrated and presented with an oversized check in front of an audience of their family, teachers and peers. That couldn’t happen this year. What also couldn’t happen was in-person, on-campus presentations of college starter gift boxes to every accepted and enrolled new student.

“These personal, high-touch interactions with our incoming class are an important part of welcoming students and getting them introduced to the campus culture,” said Piñon.

The Admissions team adjusted to the “new normal” by setting up drive-up awards. Recipients came to Heritage with their families in their cars to receive their accolades and gifts. Heritage shared their stories with the rest of the HU community through social media postings.

Despite the challenges, the outlook for new student enrollment is good. The university is on course to enroll 350 new students for fall 2020. This is 10% above last year’s incoming class.

SILVER LININGS

While the changes to business practices and academic delivery had to happen rapidly and did cause some disruption in the short-term, some of the outcomes have the potential to be beneficial to students in the future.

Dr. Kazu Sonoda, provost and vice president for Academic Affairs, points to the university’s growing ability to implement blended models of traditional, in-person classrooms with synchronous and non- synchronous course delivery.

Working from home is the new normal for Heritage faculty and staff, including Enedeo Garza III, one of our student ambassadors who work in Admissions.

“Our students have a lot of challenges and demands on their time that can interfere with their schooling. For example, a broken- down car can make it difficult for a student to get to a class,” he said. “If a student misses one or two classes, it can be challenging to catch up. Being able to provide a blended model of education, where students can attend class in real-time in person or online, or to revisit the class virtually at another time, can keep them engaged and keep them from falling behind.”

The university is working with an outside consultant this summer to make improvements to its distance learning delivery both to address the immediate needs as well as for planning for future applications.

2020/21 ACADEMIC YEAR

In late spring and early summer, much of Washington state began to see cases of COVID-19 flatten. Counties were able to move into Phase 2, meaning some businesses could start to open. However, such was not the case in Yakima County, where Heritage is situated. In June, Yakima had the dubious distinction of having the highest infection rate in the western United States. What this means for the university’s ability to return to business, as usual, remains unknown.

“We are watching this situation very closely and following the directives put forth by the governor,” said Sund. “Heritage will definitely have classes in session this fall. We’re working on contingencies for every possibility, from continuing with online courses to transitioning back into the classroom. Ultimately our goal is to provide a quality academic experience for our students so that they can remain on track to earn their degrees and begin their careers.”