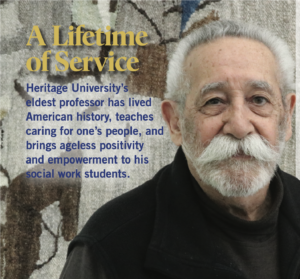

A Lifetime of Service – Wings Fall-Winter 2024

When Heritage University Professor Gregorio Ochoa walks into his first Introduction to Social Work class each semester, he writes his name and the letters “MSW” after it on the chalkboard.

“I ask my students, ‘What does the MSW stand for?’” Ochoa said. “Invariably, they say, ‘Masters in Social Work.’

“And I say, ‘It stands for “Mexican social worker.”’ Yes, I’ll tell you eventually how I got my master’s and how it all came together for me, but for now, I want you to know that part of our bond is that we’re mutually Mexican.”

That has meaning for his Latinx students in particular as they approach the work of their chosen field, said Ochoa, because their work will be all about helping people, likely fellow Latinx people.

At 70 years their senior — he turned 90 on November 20th — Ochoa is forthright about the challenges they will face. But his indomitable spirit, his cheerful way of discussing life and one’s ability to make a difference in other people’s lives is ageless.

DETERMINED TO GET AN EDUCATION

He’s lived through years of social tumult, he’s experienced plenty of racism, and he’s seen the face of actual evil up close. Yet Ochoa’s life has been filled with immense personal growth, learning, and purpose — all of which began with a very intentional pursuit of education.

Born and raised in California by a Mexican mother and Native American father, Ochoa’s parents were focused on the value of work and making a living, not education.

“My parents thought you should just get a good-paying job, like the job I had at one point working in the Wyoming oil fields,” Ochoa said. “I made $150 a week.”

It was good money at the time, and his parents thought work like that was all one needed to live a decent life, Ochoa said. But he didn’t agree.

So he joined the US Navy at 17 — knowing the GI Bill would be his path to a college education. He’d been enrolled in the seminary from age 11 to 15, during which time the value of education was instilled in him by the priests who taught him there. Ochoa eventually left the idea of being a priest behind but took the love of education with him.

He married at age 22, and his wife Donna gave birth to a daughter the next year. When she experienced severe postpartum depression following the birth, Ochoa assumed responsibility for their daughter.

“I felt I l had lost my wife to this awful thing,” Ochoa said. “She was sad and distant. I didn’t understand why, but I needed to find out.”

It would be the beginning of a lifelong interest in mental health.

FASCINATED BY LEARNING

In the college classroom, Ochoa felt intense interest in many subjects. “I was enthralled with my history course, and I wanted to be a historian,” he said. “And then I would take a biology class and was amazed by science, so I wanted to be a scientist.

“I was just moved all over the place with the learning that was going on and how interesting it all was to me.”

Ultimately, Ochoa was most fascinated by sociology and psychology. As he pursued his coursework, he also took jobs from which he could learn. During his freshman year at San Luis Obispo Junior College, he got a job as a psychiatric technician working with patients who were identified as “sexual psychopaths and the criminally insane” with the California State Department of Mental Health. It was a tough job that paid very little, he said, but he learned a lot about people and the world of psychiatric care.

He soon enrolled at California State University at Northridge and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in social work. Planning to acquire his master’s degree, he applied to eight universities and was accepted into each. He earned his Master of Social Work from the University of Southern California in 1966.

Ochoa credits college professors and mentors as well as supervisors in his various jobs with helping him along his educational and professional paths.

“I think in social work, what can make a difference is if you have a supervisor who is willing to teach what they know,” Ochoa said. “I always had that.”

Ochoa said his supervisors always seemed to want to promote him to administrative positions, but he wanted to work directly with people.

“That was and is what I love best,” Ochoa said. “What matters more to me than anything is working directly with people who need help.”

Social Work professor Gregory Ochoa talks with students following a class at Heritage University

FINDING A PLACE AT HERITAGE

Ochoa’s life’s work has taken him from California to Arizona to Washington, from senior and lead clinician positions at various mental health organizations — Central Washington Comprehensive Mental Health and the Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinic among them — to faculty positions at UCLA, Arizona State University, the University of Washington, and now Heritage since 1990.

Ochoa remembers his children’s reactions as they drove through eastern Washington State, what would come to be home for them and for Ochoa for the next 35 years and counting.

“Going over the Snoqualmie Pass, they exclaimed they had never seen so many Christmas trees,” Ochoa smiled. “And, unlike California, all the rivers had water in them.

“This was the place that was right for my family.”

A few months after beginning his work in Yakima, WA. in 1989 at Comprehensive Mental Health Services, a colleague told him she was teaching at a small liberal college in Toppenish called Heritage College.

“She said they had two classes without an instructor and asked if I might be interested in helping them out,” Ochoa said. “I asked her what the courses were, and because they were Multicultural Counseling and Family Therapy, which resonated with me and I enjoyed teaching, I told her I would be able to help them.

“I’ve been at Heritage ever since,” he smiled. “They keep giving me new contracts.”

DECADES OF CHANGE . . . SLOW CHANGE

Looking back, it can appear Ochoa has led a charmed life. He’d tell you it’s been his attitude and his strong beliefs that have made the real difference.

He discovered what interested him in life. He did well in college and succeeded professionally, having support from professors, mentors and job supervisors, and he earned advanced degrees.

Jobs seemed to come his way, with growing responsibilities and professional gratification. He was helping people he felt called to help, and he was able to make a difference in people’s lives.

But Ochoa came of age in a time that was both evolving and tumultuous — a time that had a direct effect on his life — and his determination to be of service to others through social work.

Ochoa was taught English by two nuns in elementary school where he studied. Both thought it was important to teach him English in such a way that he would not have an accent.

“So Immigration Services wouldn’t arrest me, they told me,” he said. “That’s how it was then, and it’s no different today with the political talk about gathering all the immigrants and returning them to where they came from. It’s a huge amount of déjà vu.”

In 1966, at the University of Southern California, 75 students were admitted to his class. Among them, was one Mexican, one Asian, one Native American, and one Black student. “But there were hundreds of thousands of Latinos in Los Angeles County alone,” Ochoa said. “That has changed and is different today, depending on the university.

“The amazing changes in populations in various states where half the people are Latino, that brings to bear a significant number of students that are going on to higher education. It’s hard to ignore a population that is so huge — and that is some progress.”

In 1969, in Southern California, Ochoa’s focus was on helping young people, yet that positive focus sometimes met with complications from people whose interests were malevolent. His therapy group was visited by some who sought to take advantage of people who were seeking help — among them, Charles Manson, whose cult “family” went on to murder nine people across Los Angeles over two nights.

“He came there to prey on vulnerable individuals,” Ochoa said. “I told him he was not welcome, though no one could ever have imagined what he would have gone on to do.

“My whole life I have protected the vulnerable. That is what this was.”

Social Work Professor Gregory Ochoa during one of his glasses at Heritage University

In 1971, when he visited the School of Social Work at the University of Washington in Seattle, the School’s dean was locked in his office.

“Students — Latino students — had nailed his door and windows shut,” Ochoa said. “It was an act of defiance by minority students who were not going to leave until the department hired a Latino professor.

“That was a point in time where things were changing for minority students. That dean interviewed me through a window. I had my résumé with me and handed it to him, and a few months later they offered me the position.

“Progress,” Ochoa said.

In 1989, when Ochoa accepted a supervisory position at a mental health organization in Yakima, there were two PhD-level clinical psychologists on staff. A few weeks after he’d started the job — as their boss — one of them handed Ochoa his resignation.

“I asked him why, and he said, ‘I like your ideas, but I just can’t work for a Mexican.’ I told him, ‘I have no choice but to accept your resignation. There’s nothing I can do about being a Mexican.’

“We change what we can, and sometimes you just have to accept things you cannot change, such as other people’s attitudes.”

AFFECT WHAT YOU CAN

Ochoa has waited for the world to change while changing what he can. Always he’s decided to focus on the good.

“My whole career, in every role, I focus on reality but also on possibility and fighting for what is right,” he said.

Just as his professors and other leaders helped him chart his course and find success, he works to do the same for his students as the “Mexican social worker” he is.

“It makes a difference to students to see leaders and instructors who look like them, talk like them, and have experiences like theirs,” Ochoa said. “That’s who I am, and I am here to help them.”

Ochoa believes that one of the most critical needs in social welfare/social work education today is that universities continue to hire more faculty that look like their students of color.

“Heritage does very well with this,” he said.

Not even contemplating retirement, Ochoa said his commitment to helping students learn how to protect people, especially Latinx, Native and other marginalized people, is as strong as ever.

“I see it as my commitment to social justice that sometimes people need to be confronted,” Ochoa said. “Many of our people are like lambs, and some people are like wolves, and we need to make it clear that they are unwelcome.

“That’s really the way I saw it throughout my life, and I have had to, at times, say it out loud.

“I think probably my whole life I’ve been doing that. I’ve been defending and helping people who need it.” ![]()