A Lifetime of Service – Wings Summer 2021

On her 80th birthday, Kathleen Ross reflects on how optimism, faith and persistence make all the difference in her life.

All her life, Heritage President Emerita Dr. Kathleen Ross has chosen to grow through challenges.

When serious asthma kept her indoors as a child, she learned to play piano and found the joy of music.

When she felt afraid as a pre-teen, she turned to nature and felt God’s presence.

When she was called to deepen her expertise as an educator, she uprooted herself and heeded the call to receive more education.

And when she knew that her greatest life’s work would be to build a college that could change the trajectory of thousands of lives, she did it – with an infectious joy that made everyone in her orbit want to do their part.

All her life, through challenges large and small, Kathleen Ross has found a way. Today, as she turns 80, her faith and optimism are stronger than ever.

Reflecting on the years, she said perhaps her energy level is slightly diminished.

But when your “normal” energy level has powered you through a lifetime of serving others as a nun, earning several degrees, teaching for 60 years, founding a university, and being its president for almost three decades, “less” energy is a relative thing.

She’s been published 23 times, received 50 significant awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship, and has given 70 professional presentations throughout the country. She’s been awarded honorary doctorates from Dartmouth College, Notre Dame, and Gonzaga University, to name a few.

She feels she’s better able to see the “bigger picture” in life, she said.

“I do a better job envisioning ways to get around problems. I’m more diplomatic.”

She also finds more time to savor life, taking in the beauty of nature, enjoying music and friendships.

Through all of the above, her most important identity has always been found in the initials after her name: SNJM, indicating she’s a member of the Catholic order of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary – in French: “Saintes Noms de Jesus et de Marie.”

Her most significant achievements continue to be made in service of people from underserved populations, prioritizing their education so that they, their families, and their greater community may prosper.

ROOTS OF DETERMINATION

It seems fitting that Kathleen Ross was born on a university campus. It was July 1, 1941, at Palo Alto Hospital at Stanford University, where her father was a graduate student. The son of a veterinarian and grandson of a physician, he was an international finance major. Her mother was one of 10 children born to a poor sharecropper family in Kansas. At 18, she left Kansas to study at the University of Oregon. A few years later, she borrowed money from a professor to take the bus from Eugene, Oregon, to Washington, D.C., where she trained at Walter Reed Hospital as a physical therapist. She then went to work for the U.S. Army at the Presidio.

In addition to their strong faith, Ross’s parents valued intellectual development, self-discipline, and hard work – values they passed on to Ross and her younger sister Rosemary.

Like her mother, Ross had her own challenges during childhood. She was diagnosed with asthma at age two. The family moved to Seattle for its more favorable climate.

Allergies to pollens and grasses meant finding indoor activities. Ross took piano lessons and developed a love of music. When she was in fifth grade, a new teacher who played violin and cello came to her school.

“She played for us, and I fell in love with the violin,” said Ross. “I begged my dad to let me take lessons. Finally, he said, ‘Never practice at home, and I’ll pay for the lessons.’

“So we found a way. And I got a lot of joy from playing music.”

The international tensions of the 1950s Cold War affected Ross deeply. With Boeing headquartered in Seattle, the city was considered a major target for potential Soviet aggression. Sirens would regularly sound; classes would hurry to the fallout shelter, hit the floor, covering their heads with their arms.

Ross lay in bed at night, worrying: “I was afraid an atomic bomb would kill us all.”

She learned to accept realities but not be immobilized by them.

“You have to be realistic about difficulties, but you can’t let them totally absorb your focus. You have to find a way to move to a brighter side of things, to be as optimistic as you can be.”

Ross also found peace and refuge in nature; her family camped in the Cascade Mountains.

“I learned about nature’s beauty and its resilience. I truly felt God’s presence there. I have my entire life.”

CONSIDERING HER LIFE’S WORK

Ross was nine when she first thought about becoming a nun. Her teachers, who were all sisters, often talked about how they’d realized their calling.

“The sisters’ care for others and their effective educational actions were really admirable,” Ross said.

“And, I’d been introduced to an informal, personal kind of prayer that let me listen for God’s presence and follow His input into my life situations.

“Those two things resonated with me. I thought, “Maybe I could do that, too.’”

After graduating from high school in 1959, Ross enrolled at Gonzaga University and was placed in the honors program. A year later, she made the decision to enter the novitiate, a two-year “sister training program,” at Oregon’s Marylhurst College.

She had the quiet time she needed to make her decision. At age 21, Ross took her vows with the Sisters of the Holy Names, an order devoted to educating people’s full development, with a special concern for the poor and disadvantaged.

“That time was very good for my relationship with God.”

REALIZING INJUSTICE

In the summer of 1962, Ross moved to Spokane to finish her bachelor’s degree at Fort Wright College of the Holy Names. Graduating with a history major in 1964, she spent the next six years teaching at Holy Names Academy there.

In 1970, she moved to Washington, D.C., to study for her master’s degree at Georgetown University.

She had been struck by the very Euro-centric focus on world history she found in the textbooks she’d used in teaching. She was determined to find and study what had been left out. What Ross learned at Georgetown would change her perspective on the world.

“I learned there were unique, highly accomplished cultures developed through the talents of native African, Asian, and North and South American Indigenous people that were crushed by European colonization.

“By the 20th century, millions of people throughout the world had had their ancestors’ accomplishments completely omitted from history, their own potential unmet.

“Ever since that time, I’ve looked for the hidden talents that marginalized people haven’t developed, all through lack of opportunity.”

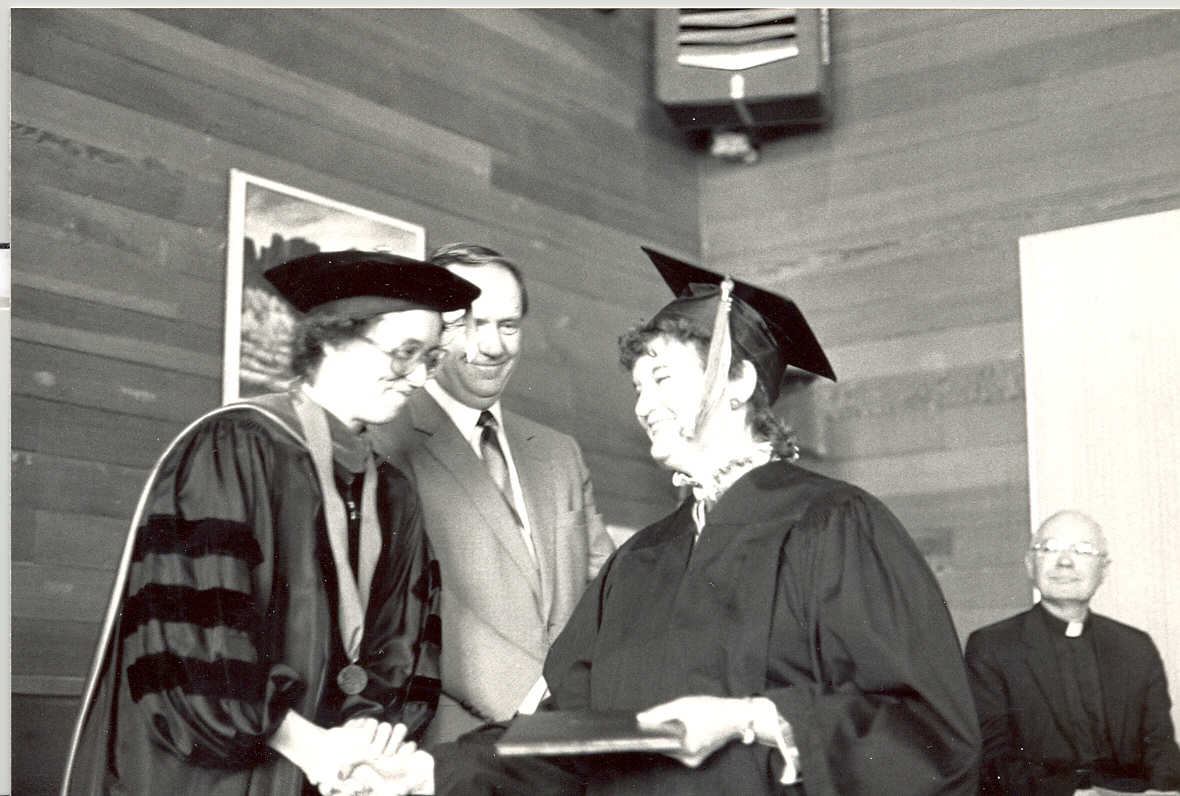

A TURNING POINT

In 1973, Ross joined Fort Wright College as its vice president for academic affairs.

Soon, two Yakama women – Martha Yallup and Violet Lumley Rau – called on her: They operated a HeadStart program on the Yakama reservation and needed help educating teachers for it. Ross made arrangements to have Fort Wright offer classes in Toppenish.

Around that time, she’d decided to pursue her Ph.D. and moved to southern California to study at Claremont Graduate University. She traveled several times to the Yakama reservation to help Yallup, Lumley Rau and others with various educational needs.

Ross wrote her dissertation on the cultural factors involved in the success and failure of Native students in higher education. It provided clear evidence that prospective Yakama students needed a college in their midst.

“If leaving your home and your people to go to college means you find yourself so challenged that you won’t succeed, you need a college that’s close to home.

STARTING “OUR OWN COLLEGE”

In spring 1980, ongoing enrollment challenges at Fort Wright made it necessary to close the college. Ross vowed to find another college for the Yakama students.

“When I told Martha and Violet, Martha said, ‘Let’s just start our own college.’

“I said that was crazy. And Martha said, ‘Tell us one thing we can’t do.’”

Ross gave them the biggest challenge she could think of: gathering a board of directors with connections and money.

A few weeks later, the women invited Ross over for a meeting. Present were the heads of a local bank and school district and two of the three county commissioners.

“There was a piece of paper on the table signed by about a dozen people who’d agreed to be the board of a ‘new private college to be named,’” said Ross.

“Martha and Violet had done it.”

“I said, ‘Dear God, you can’t be asking me to do this.’ But He was.”

Yallup nominated Ross to be the college’s president, and her new life’s work was official.

UP AND RUNNING

Sisters from Fort Wright came to advise. Board members raised funds. Fort Wright’s library books became the foundation for the new college’s library. Someone got a deal on using a local elementary school for night classes – in the building that would later be known as Petrie Hall, the anchor of the new campus.

The founders surveyed the community about what degrees to offer and hired the college’s first faculty members and administrators. They transformed the former school janitor’s house into their administration building.

Every afternoon, they moved the classrooms’ kid-size chairs aside and set up for adults.

Heritage College’s first-year enrollment was about 80, its first graduating class 85 – equally Latinx, Native, and Caucasian, majority-minority from the start.

CONTINUING TO SERVE

Today, Heritage University offers more than 40 graduate and undergradaute programs. It has awarded more than 10,000 degree and alumni are working throughout the Yakima Valley and beyond. Enrollment is steady at around 1,000.

Ross remembers hoping someday Heritage enrollment would reach 500 students.

“It’s literally twice as big as my biggest dream. And it’s recognized nationwide for its service to marginalized people.

Kathleen Ross, snjm standing at a podium delivering a few words during groundbreaking ceremony at Heritage College

“I never imagined such a welcoming campus, such beautiful buildings, such incredible board members. Or that we’d have programs that would allow our students to get their masters right here or go on for their doctorates.”

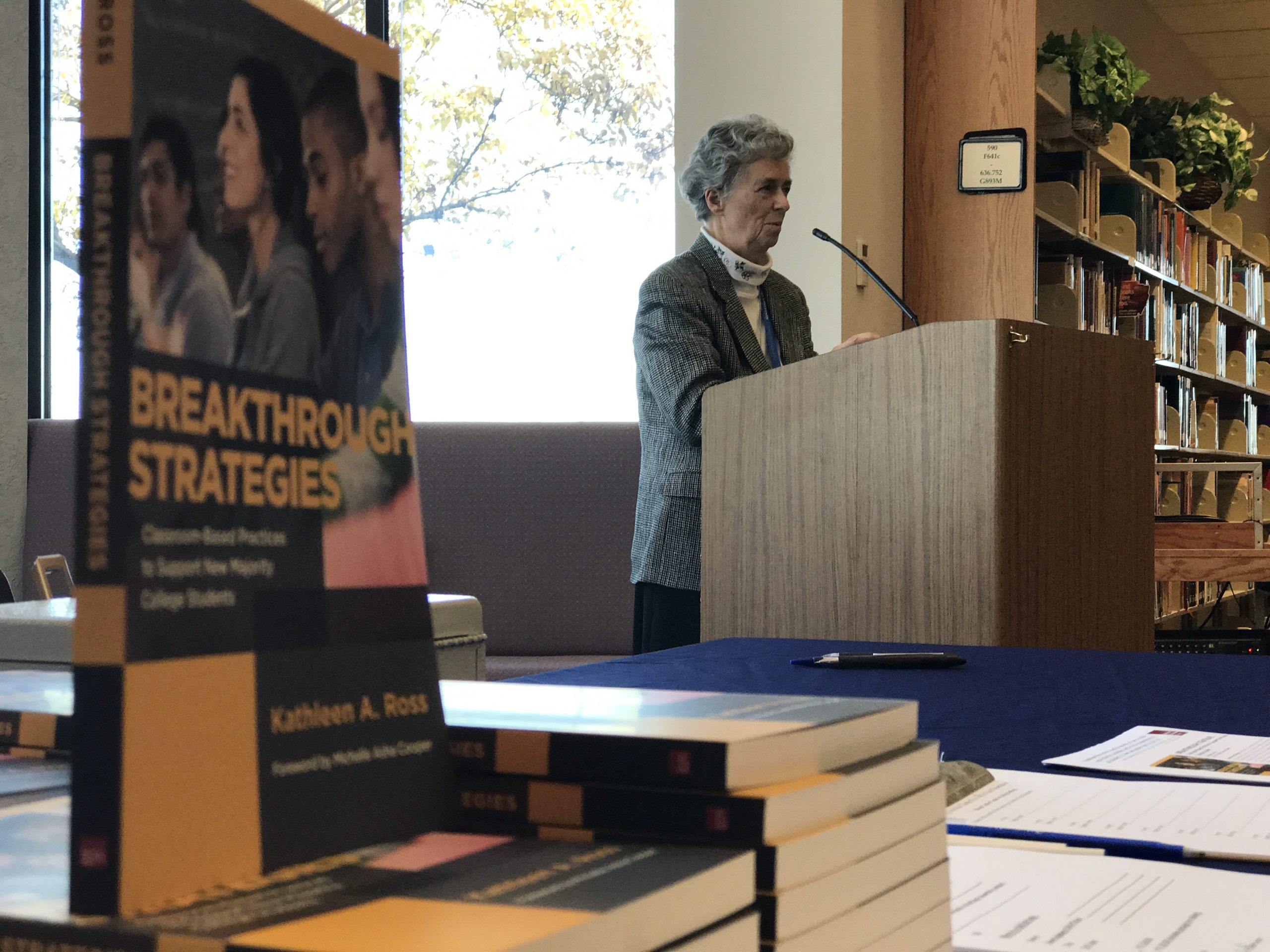

Ross is on the Heritage faculty as a cross- cultural communication professor and director of the Institute for Student Identity and Research. She works on archives projects, mentors students, and nurtures relationships with long-time university donors.

She’s happy that the university fulfills what we’re all meant to do: evolve and grow into our most fulfilled, engaged selves, to use our talents to full potential to have the best effect for others.

A little more time for herself also means renewed connection to what nourishes her spirit.

“I cook and enjoy time with my sister- housemates. I’m a lifelong birdwatcher, and I get to see so many of the birds that travel this flight path we’re on. I garden, and I’m seeing things about roses I’ve never noticed before. I can walk to Mass.”

She also plays her violin for her housemates.

The 36th annual Heritage University commencement held May 5, 2018 at the SunDome in Yakima, Wash. (GORDON KING/Gordon King Photography)

“They ask me to play the Scottish jigs – they’re their favorites.”

She smiled and said she knows her dad, who was a proud Scot, would appreciate her playing today.

Ross’s dream for Heritage’s future is simple.

Dedication of the Martha B. Yallup Health Sciences Building and the Violet Lumley Rau Center at Heritage University Sept. 15, 2016 in Toppenish, Wash. (GORDON KING/Gordon King Photography)

“We have to always respond to what’s happening in the world. I know the people who’ve dedicated themselves to Heritage’s mission will continue to meet the needs and dreams of the people we serve.

“They’ll always find a way to bring more people into the development of their talents and gifts for others.”

Heritage was planning to host several events in honor of Kathleen’s 80th birthday this fall. However, with the recent news that COVID-19 cases are on the rise, we have decided to delay these events until it is safer to gather in person. We will send out invitations to these future events once we are confident they will proceed.