Generosity for Health and Education

Gaye and Jim Pigott

GENEROSITY FOR HEALTH AND EDUCATION

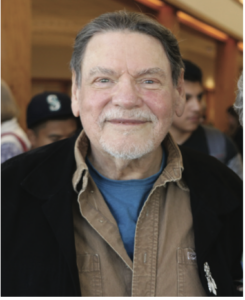

The number of lives impacted by Jim and Gaye Pigotts’ philanthropy is immeasurable. Throughout their lifetimes, they’ve supported countless organizations through their charitable giving and volunteer services throughout the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Amidst their broad generosity, two areas top their list of important causes to support–education and healthcare.

So, they were intrigued when David Wise, vice president of Advancement and Marketing at Heritage University, told them about a new partnership with Children’s Hospital of Seattle. “Good health and a good education, without both of these things, individuals will have a tough time,” said Jim.

The Pigotts invited Wise and his counterpart at Children’s Hospital, Ruben Mayes, to visit them on their ranch in Winthrop, Washington, to tell them more. The two pulled together a traveling party from both institutions: Heritage’s current president, Andrew Sund, and its founding president, Sr. Kathleen Ross, and from Children’s, James Policar, senior director of development for pediatric cancer; Doug Picha, a consultant on special projects and relationships; and Bonnie Fryzlewicz, senior vice president and chief nursing officer. The team shared how the partnership not only has an immediate impact on Heritage University nursing students who complete a four-week clinical rotation in pediatrics at one of the country’s top children’s hospitals but also how it is changing the face of nursing in Washington State.

“Heritage is a leader in higher education fostering inclusion and cultural competency,” said Wise. “Children’s Hospital is determined to help build inclusivity, diversity and accessibility within the nursing field. By working together, our students benefit by learning from world-class clinicians, and they contribute to enhanced cultural competency and situational awareness as it relates to diverse populations, which fosters growth within the Seattle Children’s staff.”

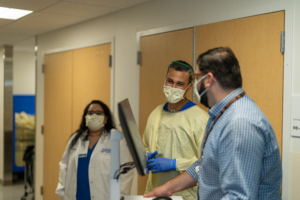

Heritage nursing students learn alongside the medical staff at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Those students, many of whom are Latinx or Native American, graduate and enter their careers, diversifying the workforce and bringing with them a broader range of perspectives and experiences, he explained.

The Pigotts were intrigued. They were already familiar with the good work being done by both institutions, having been long-time supporters of each of them. In fact, Jim spent six years serving on the university’s board of directors. Additionally, they understood the critical need in healthcare for more highly trained, skilled practitioners.

“We hear it all the time on the news: hospitals are having a hard time finding nurses, which negatively impacts the quality of care that patients receive,” said Gaye.

The Heritage and Children’s Hospital partnership addresses this need and provides the kind of hands-on training that Jim sees as critical to bridging the school-to-work gap. “This program is timely and relevant; it does a lot of what I’d like to see more of, that is integrating academia with the real world to get students working with real work situations,” said Jim.

Early this fall, the Pigotts officially announced their support for the partnership– a $4 million gift, half of which will go to establishing the Gaye and Jim Pigott Nursing Endowment at Seattle Children’s and the other half funding the Gaye and Jim Pigott Endowed Chair of Nursing at Heritage.

“This extraordinary gift will have a lasting impact on the future of pediatric healthcare,” said Dr. Jeff Sperring, chief executive officer at Seattle Children’s. “By prioritizing equity in nursing, we are taking a crucial step toward better addressing the needs of our diversepatient population.”

“Equity and inclusivity lie at the core of our educational mission,” said Dr. Andrew Sund, president of Heritage University. “This gift will empower us to expand opportunities in the nursing profession, fostering a healthcare workforce that truly represents and serves our communities.”

Both Heritage and Children’s Hospital will use the Pigotts’ gifts as the foundation for ongoing fundraising to support both endowments, which will secure the partnership program for the future. ![]()

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

A few months ago, Amazon approached Heritage with an opportunity for computer science students to work with the tech company’s project engineers to program Astro for use in museums and cultural centers. The students would add to existing programming to tailor it to museums’ needs with the goal of creating a personalized and interactive experience for patrons and the museum alike.

A few months ago, Amazon approached Heritage with an opportunity for computer science students to work with the tech company’s project engineers to program Astro for use in museums and cultural centers. The students would add to existing programming to tailor it to museums’ needs with the goal of creating a personalized and interactive experience for patrons and the museum alike.

A newly developed varietal of hop created by John I Haas and named for Heritage University is making its way into Pacific Northwest craft beers that will help raise money for student scholarships.

A newly developed varietal of hop created by John I Haas and named for Heritage University is making its way into Pacific Northwest craft beers that will help raise money for student scholarships.

Gifts to Heritage’s annual Bounty of the Valley Scholarship Dinner breaks records and tops last year’s total raised by more than $100,000!

Gifts to Heritage’s annual Bounty of the Valley Scholarship Dinner breaks records and tops last year’s total raised by more than $100,000!

Rosie Saldaña’s Heritage story came full circle this year when she was selected to paint the artwork for the Bounty of the Valley Scholarship Dinner. As an undergraduate at Heritage, she depended upon scholarships to help her fund her education.

Rosie Saldaña’s Heritage story came full circle this year when she was selected to paint the artwork for the Bounty of the Valley Scholarship Dinner. As an undergraduate at Heritage, she depended upon scholarships to help her fund her education.

2015

2015 Cialita Keys (B.A., Environmental Studies) joined the Community Development team with the City of The Dalles in Oregon, where she is working as a planning technician. Prior to this, she worked for the Yakama Nation Environmental Management as a resource coordinator.

Cialita Keys (B.A., Environmental Studies) joined the Community Development team with the City of The Dalles in Oregon, where she is working as a planning technician. Prior to this, she worked for the Yakama Nation Environmental Management as a resource coordinator.

Maria Diaz (B.A., Psychology) started a new position at the Yakama Nation Tribal School. She is the school’s new counselor. Maria spent four years prior to this working as the enrollment services coordinator at Heritage University in the Admissions department. Additionally, she earned a Master of Arts in Psychology from Fisher College in May 2022.

Maria Diaz (B.A., Psychology) started a new position at the Yakama Nation Tribal School. She is the school’s new counselor. Maria spent four years prior to this working as the enrollment services coordinator at Heritage University in the Admissions department. Additionally, she earned a Master of Arts in Psychology from Fisher College in May 2022. Brenda Lewis (B.A., Business Administration) joined Heritage University’s Admissions team in May. She is working as a transfer student admissions counselor. Prior to this, she spent two years working as a general ledger accountant for the Yakama Nation.

Brenda Lewis (B.A., Business Administration) joined Heritage University’s Admissions team in May. She is working as a transfer student admissions counselor. Prior to this, she spent two years working as a general ledger accountant for the Yakama Nation. Perla Bolaños-Zapian (B.A., Business Administration) joined the Heritage University Advancement Team as the Donor Events and Stewardship Coordinator.

Perla Bolaños-Zapian (B.A., Business Administration) joined the Heritage University Advancement Team as the Donor Events and Stewardship Coordinator.