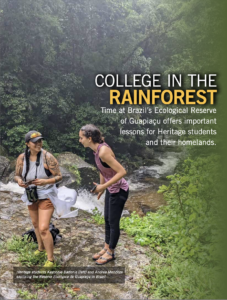

College in the Rainforest

Time at Brazil’s Ecological Reserve of Guapiaçu offers important lessons for Heritage students and their homelands.

There’s a place in Brazil where people from all around the world come to replant the rainforest, a little at a time.

They’re scientists, researchers, students and, sometimes, simply volunteer champions of the environment.

The place is Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu (REGUA) – the Ecological Reserve of Guapiaçu – and for two weeks in January, it was a classroom and an adventure for Heritage University environmental sciences major Kayonnie Badonie and biology major Andrea Mendoza. The pair traveled there with their professor Alex Alexiades, associate professor of Natural Sciences.

Returning from this journey, the students brought back not souvenirs but vibrant memories – of experiences with rainforest inhabitants, scientists working on behalf of nature and the environment, and evolving personal stories about how their own work might benefit the world.

The experience was born of a sabbatical Alexiades did two years ago.

“From that trip, I knew I wanted to bring students here for tropical field and conservation experiences and, in future visits, have them conduct research,” Alexiades said.

In his seven years at Heritage, Alexiades has worked to make several indigenous and international exchange opportunities possible for students. The experiences are powerful tools for engagement, he said.

“Once students have experienced this environment and the work people do, they can think about its ramifications for the places they love and care about in their own communities.”

BATTLE FOR THE AMAZON

A 2.5-hour drive northwest of Rio de Janeiro, the Guapiaçu area is located on the border with the state of São Paulo in southeast Brazil.

It holds incredible biodiversity – the first reason Alexiades chose to work there. His second reason – the mission and the effort being made to return the area to its natural state and support its inhabitants, both human and non-human – is why he thinks it’s important to come back.

In the native Tupi language, Guapiaçu means “big spring of a river.” But the river here, like the rainforest that holds it, has been greatly altered, its banks laid bare for farming and grazing cattle, its flow in part channeled for human use, sometimes reinforced with concrete.

In the native Tupi language, Guapiaçu means “big spring of a river.” But the river here, like the rainforest that holds it, has been greatly altered, its banks laid bare for farming and grazing cattle, its flow in part channeled for human use, sometimes reinforced with concrete.

Surrounding land, once lush and green, has been logged, tree stumps burned, remaining vegetation removed to make room for subsistence farming and, in some areas, hydropower dams, mining and other development.

Where crops were once planted only to fail in the acidic and largely non-fertile soil, cattle graze on barren riverbanks, eating any remaining native plants, consuming grass almost as quickly as it can grow back.

Where natural forestation provided environmental balance, today’s riverbanks offer no resistance to the flooding that occurs almost daily during the months-long rainy season. Mudslides are common, and life is continually unsettled.

“What’s been allowed to happen to the rainforest disrupts everything from the ecology to the hydrology,” Alexiades said. “This is really an ongoing battle for tropical rainforests worldwide.”

THE REGUA SOLUTION

The REGUA land, owned by what had been a tobacco- and banana-growing family for several generations, comprises almost an entire watershed. Through an evolving commitment to protecting the biodiversity of the valley, recent owners saw the need to ensure the future of their community through reforestation. The majority of their land has now been replanted and reforested.

Efforts now also focus on land buys to conserve additional land. Eventually, they will reconnect the watershed all the way to the river’s mouth, about 65 miles south into the city of Niterói.

REGUA’s work has meant about 60 full-time jobs – from cooking and cleaning for visiting groups to the main work of tree planting – added to the local economy. It’s a model for engaging communities in tropical rainforests worldwide.

EXTENDING THE EFFORT

Relative to the immensity of the rainforest, the work being done at REGUA is small scale. Yet, Mendoza and Badonie learned it’s making a difference for the people, animals and plant life in the Guapiaçu area and has implications for other deforested areas of the Amazon.

“The restoration is not only helping to repair the river, it’s also bringing back important rainforest habitat that was once destroyed, and species are returning,” said Mendoza.

“It’s inspiring to know that if we work together with people, we can see a true change in this world for the better.”

Both students felt the hope the REGUA reserve could be for other areas in the rainforest, and that its work is making people’s lives better in the immediate area and downstream.

“What is being done in the REGUA vicinity is fascinating,” said Badonie. “It’s scientists, researchers, and passionate community members coming together to combat deforestation and land disturbance.

“I believe that this is a start for the forests and streams and a healthier environment.”

STUDENTS ABSORB LESSONS

There’s a community that’s formed with each set of scientists, researchers and students who come to work and study at REGUA. So when heavy January rains kept everyone from the intended data collection and tree planting, Badonie and Mendoza

got to spend invaluable time talking with and learning from the visiting ornithologists, entomologists, and mammalogists that surrounded them.

At day’s end, they’d gather, sharing photos of plant and animal life, watching trail cam videos. Beyond being awed by the color of birds, the size

of insects, and the sheer volume of rainforest sounds, the students were fascinated by the wealth of knowledge around them.

Two decades ago, working as a high-altitude mountaineering guide in the Andes, experiencing the mountains’ majesty and the regalness of the rainforest as well as its rampant destruction, the trajectory of Alexiades’s life was clarified. His immersion experiences steered him to acquire his master’s degree and his Ph.D. His goal now is to research the whole Guapiaçu watershed, comparing the quality of its water today with the improved water quality that’s certain to come.

Badonie, a Yakama tribal member with Navajo Nation roots, said her time at the reserve is already helping clarify her path.

“For me, it hits home because native lands were disturbed by agriculture, and that’s something from which we can never turn back. So if I can take something of what I’ve experienced to the tribes, that will mean a lot.”

Mendoza wants to teach science and inspire younger generations to enjoy it, pursue its study and change the world.

“I can tell them this is what I got to do in Brazil, to help people with their land and their lives,” she said. “This is what you can do in an internship.”

“I think I can inspire them, like I’ve been inspired. The world needs this work and the people who are doing it.”