Instruction Coming from Around the World – Wings Summer 2021

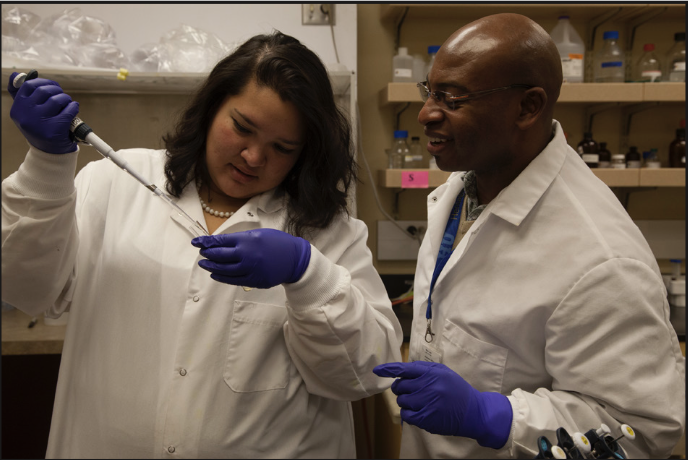

Melvin Simoyi knows all about humble beginnings and the rewards of hard work and persistence.

“I was raised in a rural area in Zimbabwe – dirt roads, water from a well, no electricity, gas lamps and candles. I was an only child but had many cousins. My grandparents were farmers growing corn, carrots, tomatoes, and right in our yard were guavas, mulberries, mangoes, peaches, pomegranates. We were not rich, but we had everything we needed. I would sell avocados, then go downtown to watch a movie with the money I earned.”

Simoyi went to an all-boys school. His father, a physician, wasn’t involved in his life until he was 13. That relationship ignited an interest in entering the medical field as either a doctor or a veterinarian. After graduating from secondary school, he enrolled at the University of Zimbabwe and studied animal science. He then turned his sights to the United States for graduate studies, enrolling in West Virginia University. There he earned both a master’s degree in veterinary science and a Ph.D. in Avian Biochemistry and Physiology.

After completing his graduate studies, Simoyi’s career path started in the pharmaceutical industry, where he performed pre- clinical antipsychotic drug research. Because his then wife was in medical school and they had to move frequently for her studies, he worked in several different industries and research projects. He started out working for Sanofi-Aventis (at the time Aventis before the merger with Sanofi) Pharmaceuticals researching antipsychotic drugs. Afterward he went to the University of Pittsburg psychiatry department, where he researched nicotine addiction using a self-administration rat model. Then it was on to studying mitochondrial disease at Columbia University’s neurology department. Afterward he spent two years working as an assistant medical director for a medical education company writing promotional scientific materials for pharmaceutical clients. At the completion of her medical school, his then wife’s career brought them to Washington state, he then made the leap into academia. He started teaching a few science courses at Heritage as an adjunct instructor. A year later, he joined the faculty full- time and took on the coordination of the McNair Program.

The McNair Program is a federally-funded program designed to prepare low-income, first-generation and minority students to pursue graduate and Ph.D. studies. Students in the program receive paid summer research internships, mentorship and advanced research opportunities, among other benefits—Programs like McNair level the playing field for students who, like him, came from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“Disadvantaging minorities and racism are woven into so many systems in the U.S. It suppresses people of color, while others have an unfair advantage. But our programs at Heritage can and do make a difference,” said Simoyi. “Education levels the playing field. However, often there is nobody in our students’ families who they can talk to about going to college, let alone graduate school.. Through the programs that I oversee, including the Title V programs that build capacity/programs at Hispanic Serving Institutions, we expose students to the world so they don’t feel like they haven’t had the life experiences other students out there have had. They find success and feel like they belong. Things like this make a huge difference.”

That’s not all, said Simoyi. Having mentors who look like you or come from similar backgrounds or have had similar experiences and have achieved the success that you desire can be a very powerful motivator.

“I share my story with my students. They know where I’ve come from and how hard I’ve worked to achieve my American dream. My story gives my students hope for their own futures. It demonstrates the power of education and what taking advantage of opportunities that come your way can do.”

Kobe, Japan, is about as far away from Toppenish, Washington as one could imagine. This bustling city of more than 1.5 million people is located on the main island of Honshu, on the north shore of Osaka Bay. It is a port city dependent upon manufacturing and exporting and home to some of Japan’s largest corporations, such as Kawasaki, Mitsubishi Motors, and Kobe Steele. And, it is the hometown of Heritage’s Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs, Kazuhiro Sonoda.

“My father was a doctor, and my mother was a housewife. I grew up in an upper-middle-class home and was told I could be anything I want when I grow up. In the 1970s, Japanese schools were very competitive, and I didn’t study at all, so I had no chance of making it in the Japanese school system. My family and I decided that I should finish my high school years in the United States.”

Two of Sonoda’s aunts were “war brides” who had married American servicemen after World War II. They were living in Los Angeles and Oxnard, California. He moved in with one of them when he was 15 and stayed until he graduated from high school.

“Growing up, I was always around microscopes, and I was into fishing and birds,” said Sonoda. “Science was a natural path for me to study.”

He stayed in the United States, enrolling in San Jose State University, where he majored in marine biology with a minor in chemistry and business finance. His interest in coral reefs and the marine life that inhabits those areas took him to the University of Guam, where he earned both a Master of Science in Biology and a Master of Business Administration.

“It was the best time of my life. I loved the island style, the beach and the endless summers,” laughed Sonoda. “I had many opportunities to visit various islands in Micronesia, and I start to realize the effects of human impacts on coral reefs. My interests shifted from biology and ecology to environmental issues and human impacts on the ecosystem.”

Sonoda wanted to move into higher education and started looking for doctoral programs with an environmental science focus. It was the early 1990s, and the field was relatively new. Portland State University was one of a few universities with a doctoral program in environmental science. He enrolled and focused his research on urban hydrology, aquatic chemistry and water quality issues. After completing his Ph.D., he joined the faculty at Tokai International College in Honolulu, Hawaii, where he taught math and science. Two years later, he was the college’s Dean of Instruction.

It wasn’t long before Sonoda exchanged his metropolitan, island lifestyle for a slightly less urban, desert existence. His wife, an engineer, was offered a position at Northwest Energy in Richland, her hometown. It was 2007, and Heritage University was expanding its faculty and looking for an associate dean of Arts and Sciences. It was one of those meant to be moments where the right person and the right opportunity aligned perfectly. Sonoda was offered and accepted the position. A year later, he was promoted to dean.

A few years after that, he was the associate provost. Today, he is the Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs.

With all of his own personal accomplishments, it is the accomplishments of his students that give Sonoda some of his greatest rewards.

“When I was a professor, I got to help my science students see themselves be more than they ever imagined, to do things they never thought possible, and to take their hard work and research to the national stage and be recognized for their successes. As provost, I get to see every student who graduates go on to make real, positive changes for their family and in the world.”

He credits some common bonds that help him connect with students and build relationships with them that help them to succeed. One of which is the challenge of learning when English is not your first language.

Kazuhiro Sonoda at a recent Heritage University commencement ceremony at the Yakima Valley SunDome in Yakima, Wash.

“I believe how you grew up creates your worldview, and I understand our students’ perspective. There’s never just one side or one way of seeing things,” he said. “With English being my second language, I know that for many Hispanic students, learning English and new concepts at the same time is a challenge. At Heritage, we recognize students’ backgrounds and try to meet them where they are. My background allows me to be accepting.

“I also see that Japanese Shinto beliefs and Native American beliefs are very similar. Both see nature as one. There is respect for water, air, soil and animals. We’re going back to that. Western science has studied nature by dissecting it, but now we’re trying to incorporate this more traditional sense of oneness into our curriculum. It feels good to be doing this work.”

He also credits his dual academic pursuits–business and science–in helping him prepare students for successful careers.

“The needs of businesses and the interests of science are two different sides of environmental issues. We need to keep in mind both sides of the issue when working towards solving problems. This is something that I teach my students and encourage them to be mindful of this when they enter their careers. We will all be better for it.”

John Tsiligaridis is a humble man who would never dream of describing himself as brilliant. However, that is precisely how friends and colleagues describe him, that and being extremely dedicated to his students. He holds half a dozen degrees, including two PhDs, two master’s degrees and two bachelor’s degrees. He speaks four languages. He is internationally recognized for his work on scheduling, mobile databases, wireless networks, data mining, text mining, networking, bioinformatics, and genetic algorithms. He has more than 60 published works in his name. And, in his students’ eyes, he is a rock star!

Tsiligaridis was born in Thessaloniki, Greece, a city founded in 315 B.C. He lived in the city and spent summers with extended family in a village near the mountains. There were farms and a river, and he enjoyed playing outside with his cousins.

“Education was the most significant component of my upbringing. Early on, I developed a love for math and sciences. I also appreciated art, and I liked painting and enjoyed the ancient Greek sculptures. My parents supported my desire to learn foreign languages, so I learned French, Italian, and English,” he said.

Tsiligaridis’s academic pathway began in the early 1970s with the first of his bachelor’s degrees. Over the next 30 years, he amassed six degrees at universities in three countries. His two doctorate degrees, one in Electrical and Computer Engineering with a focus on computer networks from the National Technical University of Athens in Greece, and the other in Computer Science and Engineering with a focus on networking, scheduling, and computations from the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, were earned nearly a decade apart.

It was the invitation from the University at Buffalo where he earned his last degree that sent Tsiligaridis on the pathway that brought him to Heritage. The initial plan was to complete a few years of study, then return to Europe.

“My wife and our school-age children came to stay with me until I was finished, but in the end, no one wanted to go back! We were thrilled to meet people coming from many different parts of the world. It was a real multicultural environment. We also loved U.S. schools and the progress and opportunities they offer to students. We decided to stay and seek employment in academia here,” he said.

Around that same time, Heritage University was conducting a national faculty search for a professor to teach computer science.

“Initially, I was willing to relocate to Washington state because this area is very children-friendly with lots of outdoor activities and schools that can offer personalized attention,” he said. “The more I learned about Heritage, the more I wanted to teach there. I liked everything about the university! The people, the area, and especially the culture of the university – the inclusiveness, respect, support, and very nice faculty and staff all encouraged and inspired me to do the best job possible. H.U. is a unique place with a diverse student population. It made me want to be a part of this community and to do my very best to help its students achieve and excel.”

This is what he does best, and it starts at the beginning of their studies.

“Most of the students coming to our program have no prior experience or background in computer science. We have to familiarize them with the subject, show them the way of thinking in this new area for them to facilitate their learning. Depending on the student’s abilities, special support and extra help go a long way,”

he said. “Varieties of support materials, practice, hands-on programming, etc., are valuable tools that help our students understand and grow in this field of study. And, every computer science student is placed into at least one research or internship experience.”

It is through his students that Tsiligaridis finds his greatest success and best rewards.

“I feel extremely happy when former students come back to me or send a thank you email, sharing their experience on how well what they learned here at H.U. serves them in certain situations in their jobs. Sometimes they mention a particular thing I taught in class that they found very useful in their new job,” he said. “Their success gives me great satisfaction, and I am very proud of their efforts and achievements.”