Just Tell Us One Thing We Can’t Do!

It was spring 1980 when this simple sentence ignited the idea that put into motion the actions that launched Heritage University.

The story of the little university that could goes back to the mid-1970s when Martha Yallup and Violet Lumley Rau decided the Yakima Valley needed access to higher education. The two reached out to Fort Wright College in Spokane, a Catholic school operated by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. The college had an extension program that brought credit-bearing courses into rural communities. Yallup and Lumley Rau convinced the administration at Fort Wright to bring classes to Toppenish.

By 1980, ongoing enrollment issues forced Fort Wright to close its doors. Then provost Sr. Kathleen Ross traveled to Toppenish to deliver the news about the closing in person. Neither Yallup nor Lumley Rau were willing to let their community go without access to education. When Ross suggested she would find a replacement university for a similar partnership, Yallup told her they would start their own college. When Ross realized the enormity of that initiative, she told the pair the first thing they needed to do was form a board of directors with community leaders who had connections and could help find the funding necessary for a project of this magnitude. Yallup uttered her now- famous words, “tell us one thing we can’t do.”

Yallup and Lumley Rau didn’t waste a moment. Within a matter of weeks, they had their board of directors. They asked Ross to serve as the college’s inaugural president.

To an outsider, the formation of Heritage College, as it was then called, seemed like a project doomed to fail before it even got started. After all, who would build a college in the middle of a hop field, in a community where the high school dropout rate was higher than the college attainment rate, and during a global recession, nonetheless? Yallup, Lumley Rau and Ross were determined. They knocked down every roadblock that threatened their progress.

A year after the meeting that would have ended college classes in Toppenish, Heritage started operating under the umbrella of Fort Wright. The following year, 1982, it officially began operating under its own power as a private four-year college.

From the beginning, Heritage was an institution like no other. Its mission was, and is, to serve those who had traditionally been left out of higher education—older students, first-generation college students, minorities, and those from low-income households. Heritage opened its doors with 85 students and eight faculty and staff members. Most of the students were older with families and responsibilities beyond their schooling.

Over time, the university grew. It acquired the land upon which it sits today. Capital campaigns raised funds to build buildings for the library, classrooms, offices, student services and a dining commons. Degree programs expanded to include majors in social work, the sciences, humanities and healthcare, and the education and business programs already in place. The name changed from Heritage College to Heritage University to more accurately reflect the level of education provided.

Moreover, the student body grew and changed. By 2010, the average age of a Heritage student dropped from 35 to 28. Today, it is 24.

What has not changed is the university’s mission. Heritage remains grounded in its commitment to ensuring that college education remains accessible to all, regardless of social, cultural, economic or geographic barriers. That mission calls to people and attracts educators from around the world who seek out Heritage for the opportunity to work with its students, and propels those who recognize the power of education to change lives and communities for the better to support the university and its students.

1974 – Fort Wright College starts offering college credit-bearing courses at a remote campus in Toppenish.

1980 – Fort Wright College announces it will close in 18 – 24 months due to financial losses. Martha Yallup and Violet Lumley Rau convince Sr. Kathleen Ross to join them in starting Heritage College.

1981 – Heritage begins offering its first classes as the Heritage Campus of Fort Wright College in a facility rented from the Toppenish School District.

1982 – Heritage College officially opens the day after Fort Wright College officially closes, with 85 students and eight faculty/staff members and official candidacy status from the accrediting association. The first academic offerings include bachelor’s degrees in education, interdisciplinary studies and business administration, and a master’s degree in education.

1984 – Petrie Trust funds the acquisition of the 14- acre Heritage campus to include the former McKinley Elementary School building.

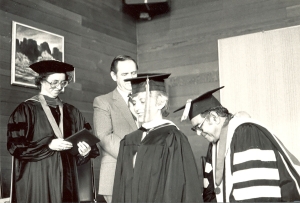

1985 – The first class of Heritage College graduates receive their degrees a ceremony held at the Yakama Nation Cultural Center.

1989 – Heritage University is one of two colleges nationally to receive the American Association of University Women’s “Progress in Equity” award. It grows to a student body of 540, 39 full-time and 60 part-time employees, and 330 graduates.

1993 – Heritage University dedicates the new Library and Learning Resource Center, now called the Kathleen Ross, snjm Center, made possible through a $7 million capital campaign.

1995 – Heritage graduates the 1,000th student, and enrollment tops 1,000.

1999 – Heritage remodels the old McKinley Elementary School to include classrooms, a bookstore, and a student lounge, christened the Jewett Student Center. The building is renamed Petrie Hall.

2001 – Heritage College dedicates its first Student Services Center, a 5,050-square-foot facility.

2003 – Heritage opens a regional site at Columbia Basin College in Pasco, Washington, and starts offering bachelor’s and master’s degrees at this location.

2008 – Heritage raises $27 million in the Heritage for the Future campaign and opens its 35,000 square foot Arts and Sciences Center.

2009 – Dr. Ross announces she will be transitioning from her position of the university president to pursue the formation of a national institute housed at Heritage.

2010 – Dr. John Bassett, former president of Clark University in Massachusetts, is appointed the second president of Heritage University.

2012 – Petrie Hall, the former McKinley Elementary School, is destroyed by fire.

2014 – Heritage opens three new buildings: the new Petrie Hall, with an art gallery, art studio and classrooms; Rick and Myra Gagnier Hall, dedicated to information technology; and the Gaye and Jim Pigott Commons, which houses the cafe and lounge.

2016 – Heritage opens two new buildings named in honor of the university’s founding mothers, the Violet Lumley Rau Center, which houses the university administrative offices as well as its largest classroom; and the Martha B. Yallup Health Sciences Building, which houses offices and a large classroom.

2017 – Dr. Andrew Sund joins Heritage as its third president. He was previously president of St. Augustine College in Chicago, Illinois.

2019 – Heritage forms the workforce development program Heritage@ Work, which provides customized worker training for employers in the university’s service area.

2020 – Heritage leads a partnership of nonprofits and educational organizations to form Yakima Valley Partners for Education, a “cradle to career” initiative to improve academic readiness and success for children in the Yakima Valley.

2022 – Heritage celebrates 40 years of making higher education accessible in the Yakima Valley.