Saving the Language

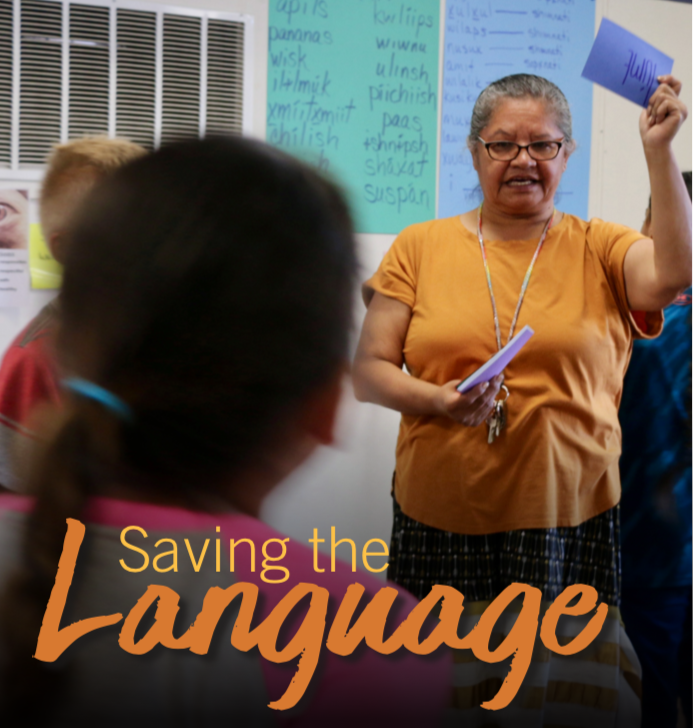

Zelda Tinnier leads kids from the Yakama Tribal School through Ichishkíin language exercises during the Yakama Nation’s Summer Language Boot Camp.

“IF WE SPOKE OUR LANGUAGE, THE TEACHERS BEAT US. SO LATER, I NEVER WANTED TO TEACH MY CHILDREN. NOW, I REGRET IT.”

In those few words, Gregory Sutterlict’s great- grandfather told of the deeply felt grief among Yakama elders over losing their native language.

Today, Sutterlict, the Mellon-endowed chair of Heritage University’s Sahaptin Language Department and Director of the Heritage University Language Center (HULC), is part of a contingent of Yakama people, schools and organizations working to revitalize the language.

The Ichishkíin Language Alliance teaches the Yakama native tongue to kids in kindergarten through grade 12 and beyond – where the future of the language lies.

The Alliance is comprised of educators, elders and leaders from the Yakama Nation, area school districts and the university. In addition to Heritage, it includes representation from the Yakama Tribal School, the Mt. Adams School District, the Zillah School District, the Yakama Nation Sahaptin Language Group, the Wapato School District, Yakama Nation Headstart and many individuals.

It’s important work: Ichishkíin has been at risk of “endangerment” for several decades.

There are nine stages of language endangerment, said Sutterlict, and in the late 20th century, Ichishkíin was at the stage linguists call “no one under child-bearing age” speaking the language. When young parents don’t know the language they can’t teach their young children, and the language dies. But a language can be revived. With work, it can be brought back to life.

FOLLOWING IN ELDERS’ FOOTSTEPS

Suttlerlict remembers hearing Ichishkíin as a boy along with the stories and lessons of the elders. He always wanted to learn more.

As an undergraduate, he took classes at Heritage, studying under Virginia Beavert, who holds two Ph.D.s in linguistics and is the author of The Sahaptin Practical Dictionary for Yakama, considered the most advanced volume on the Ichishkíin language.

Beavert’s stepfather, Alexander Saluskin, whose Yakama name was Chief Wiy’awikt, spent his life chronicling the language. When his health declined, he prevailed upon Beavert to take up the gauntlet and continue his work. Beavert wrote the dictionary with co-author Sharon Hargus, a linguist at the University of Washington. A second volume is currently in the works.

Beavert’s stepfather, Alexander Saluskin, whose Yakama name was Chief Wiy’awikt, spent his life chronicling the language. When his health declined, he prevailed upon Beavert to take up the gauntlet and continue his work. Beavert wrote the dictionary with co-author Sharon Hargus, a linguist at the University of Washington. A second volume is currently in the works.

“The book is not just a dictionary, it’s grammar, morphology, phonology, semantics, phonetics – everything. It’s one of the top 10 books of its kind ever,” Sutterlict said.

Sutterlict earned his bachelor’s degree at Heritage in 2004 and did his master’s work in linguistics at the University of Washington. He’s currently working toward his Ph.D. at the University of Oregon.

Sutterlict’s work and the work of the Alliance focuses on language preservation, revitalization and promotion.

“Preservation is documenting things. Revitalization is bringing it back to life. And promotion is putting it out there into the community,” said Sutterlict.

“Promotion is why we’re on Facebook and why we do YouTube videos – so everyone can access it, so teachers can use it in their classrooms, people can watch it, everyone can access it.”

Olivia Underwood, left, and Marvel Aguilar learn Ichishkin (the Yakama Indian language) in a class July 18, 2019 in White Swan, Wash. (GORDON KING/Gordon King Photography)

TEACHING HERITAGE AT HERITAGE

Members of the Alliance are passionate about the work they do. Classes are held at schools throughout the Yakama Nation and in its surrounding communities. For its part, Heritage’s initiatives include:

• An Ichishkíin-focused 2- and 3-year-old classroom at the university’s Early Learning Center

• College-level Ichishkíin classes, which are also open to the Yakama community to attend free of charge

• The Zillah after-school Ichishkíin Language and Culture Club providing an opportunity to use Ichishkíin in conversation, games and presentations

Sutterlict teaches “Sahaptin101” and “Sahaptin 102” each semester – “Sahaptin” is the scientific and English word for the Ichishkíin language – and estimates that anywhere from 10 to 20 students take the courses and can speak, read, and write the language by the end of the year.

Some Yakama elders still speak Ichishkíin but don’t write it. Sutterlict’s students are typically able to listen to an elder speak and then write what they’re saying.

FROM ELEMENTARY TO HIGH SCHOOL

Natural language-learning geniuses: That’s what Sutterlict call kids.

“All they need is exposure to it, and they get it,” he said. “After puberty, only about 10 percent of us retain the ability to easily learn a language.”

This is why members of the Alliance concentrate their efforts on youth activities. Sutterlict and others teach children using pictures of things, skipping any reference to English words.

“For little kids, it’s seeing and hearing, verbal and repetitive,” he said.

For grade school students, teachers, parents and community volunteers help organize Ichishkíin language competitions, helping with PowerPoint support and judging. Think “spelling bee” but with pictures to encourage answers.

The steady groundswell of support even led to a Yakama Nation supported, month-long Ichishkíin “boot camp” this summer that was run through the tribe’s youth programs. Children from pre-school through middle school spent several hours a day learning the language through a combination of reading and writing exercises, as well as traditional teachings, such as storytelling, song and beading. The idea was to immerse the children in the language through activities that engage them in the learning process.

Alliance members would love to see all Yakama kindergarten-age children learn Ichishkíin.

“We don’t have an elementary level at the tribal school, but that would be a dream come true,” said Sutterlict.

Roger Jacob and Rosemary Miller, both of whom studied under Virginia Beavert at Heritage, teach Ichishkíin at Wapato and Toppenish high schools, respectively. Prior to 2010, there was no Ichishkíin taught in area high schools.

Like the other organizations in the Alliance, Jacob and Miller utilize the learning materials created for Alliance use.

Between the two high schools, 15 to 20 students graduate able to speak Ichishkíin.

Pre-kinder students touch a stuffed toy sturgeon held by Greg Sutterlicht as he teaches Ichishkin (the Yakama Indian language) to the youngsters July 18, 2019 in White Swan, Wash. (GORDON KING/Gordon King Photography)

KNOWING THE CONNECTION

A few years ago, Greg Sutterlict sat on a panel at a Seattle event discussing language. Someone mentioned a universal language would be nice, that easier communication would make life simpler.

“I said ‘I hope we never think of language as being only a communication tool. The fact is language and culture can’t be separated. Language is part of what helps us know what’s important to our people,’” said Sutterlict. “Our young people need to know our language and our history instead of how it’s always been told. I want our children to know and love their culture, a very old culture that’s extremely connected to the land, to the animals and the food, one of respect and honor for them as well as ourselves and our families. Our language speaks of all of that.”

ROOTS GET STRONGER

“My dad tells us, ‘When I was a kid, no one wanted to speak Ichishkíin. No one wanted a braid. Now they want to learn, and they want a braid,’” said Sutterlict. “Today, when my students sing Ichishkíin songs, other students hearing them ask to sing, too. At home, the children sing the songs they’ve learned.

“I tell new students, ‘Repeat after me, Wash nash Yakamaknik. I am Yakama,’” he said. “They learn the language and sing the songs. When they start to learn their culture, you can see the change. Their roots get stronger.”