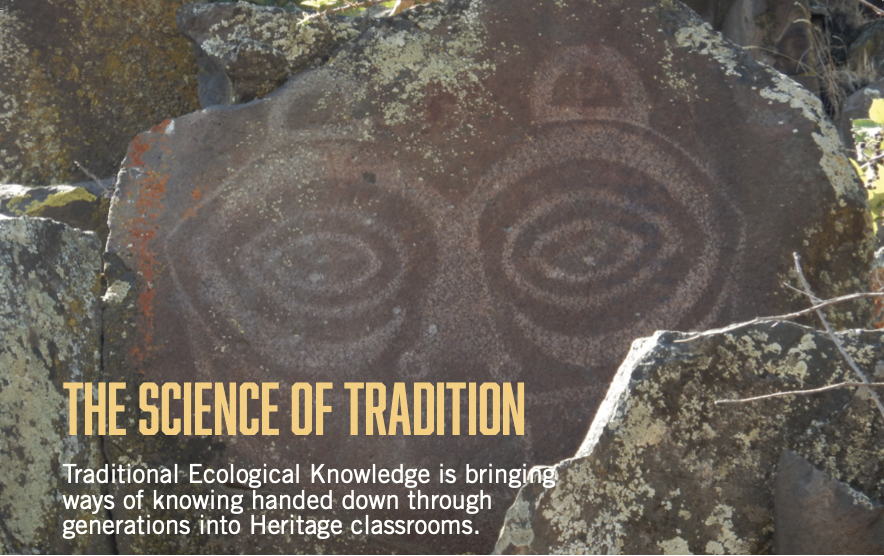

The Science of Tradition

When Environmental Sciences student Agnes Meninick was completing her internship project last summer, she had no idea she was engaged in a relatively new method of science teaching and learning. An educational movement incorporating Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) into western science curriculums is finding growing support on college campuses. Heritage University is at the forefront of this movement.

“Traditional Ecological Knowledge is a recognition that the people who have been on these lands, whose lives have been deeply connected to their environment, since time immemorial, have a voice and a perspective that deserves to be heard,” said Dr. Jessica Black, chair of the Sciences Department. “It is bringing those voices into the classroom and our students’ experiences.”

While TEK may sound like a radical departure from the way science curriculum is traditionally taught in colleges, Black explains that it and western science are not mutually exclusive. They complement each other, especially when it comes to the field of environmental science.

“So much of western science is based on concepts held by indigenous peoples throughout the world,” she said. “There are many areas where western scientists can’t collect data. In these areas, indigenous populations are the knowledge holders. They have historical perspectives that western science lacks and often have an innate understanding of how organisms and ecosystems interact.

“Native American tribes are leading the way on much of the work around conservation and environmental protection and policy. They need graduates who are western science trained, but who also have a real respect for tribal practices.”

Take the work being done by tribes in Washington state around salmon restoration, for example, said Dr. Alex Alexiades, associate professor of natural science.

The Columbia River Basin is the traditional fishing ground for the Yakama people. Starting in the mid-1930s and running to the 1970s, the Army Corp of Engineers built hydroelectric dams up and down the river.

“From the western perspective, the dams brought reliable, clean power. However, from the tribal perspective, they disconnected the sacred river and the species that require the use of that watershed,” he said.

Indeed, the dams did provide power, but the unintended impact on fish that could no longer reach their spawning grounds was devastating. Salmon populations declined rapidly.

“The tribes have and continue to take a central role in finding solutions to mitigate the negative impact that dams made to the salmon population,” he said.

Alexiades stresses that while students who study in programs with a TEK focus are better prepared for careers working with tribal agencies, far more significant benefits positively impact all students, regardless of their career destinations. He explains that western science tends to look at things at a granular level—a geologist studying a specific rock or a biologist concentrating on a single species, for example. However, in nature, all of these pieces are elements within a larger whole of the ecosystem. They all relate to each other, and what happens to one impacts others. TEK is a reverence and understanding of all of the elements of the environment and recognizing the need for a more holistic approach when working within the environment.

TEK IN THE CLASSROOM

Integrating TEK into the environmental science curriculum was both intentional and collaborative. When Dr. Kazuhiro Sonoda, provost and vice president for Academic Affairs, came to Heritage and became dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, he enlisted the help of Black to introduce TEK to the curriculum.

“Heritage is located on the ancestral tribal lands of the Yakama people. Our strength is our location and our relationship with the Yakama Nation,” he said. “Building the program began with our relationship with the tribe, with being intentional and respecting the culture.”

The university built its relationship with tribal elders, scientists and leaders within the Yakama Nation’s environmental programs. They were invited into the classrooms to share stories and to talk about the work they were doing. Students were placed in internships and research experiences with tribal agencies. Additionally, Heritage developed intergenerational programs that connected high school students with college students, tribal leaders and elders, such as its annual People of the Big River class that takes students on a two-week academic excursion to visit tribes up and down the Columbia River Basin. That work continues today.

Sonoda stresses that TEK isn’t a substitution for western sciences; it is an addition. Students still participate in rigorous biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics curriculum, just with a broader perspective.

TEK OUTSIDE OF SCIENCE

TEK may have started the environmental science program, but it is expanding into other programs.

A little over a year ago, Sol Neely. Ph.D., a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, joined Heritage’s English Language Arts faculty. He is currently the director of English composition. He is working with Humanities Program Chair Dr. Blake Slonecker on revitalizing the university’s American Indian Studies program into something he calls a “transdisciplinary studies program.” TEK, he says, plays a role in academia across curriculums.

“Indigenized work isn’t divided into disciplines,” he said. “When you look at a bentwood box being made by a Tlingit artist, the person working on the box is as much a scientist as he is an artist. He has to have all the biological knowledge about the wood—the cell structure, how to store it, how steam works to soften it so it can bend. All of these endeavors go into crafting the box that tells the stories.”

He explains that ensuring that American Indian Studies students get a complete, well-rounded education on the Native experience means they will need to study a wide array of disciplines through the lens of indigenous peoples.

A STUDENT’S EXPERIENCE

Meninick is enrolled Yakama and a junior majoring in environmental science who hopes to one day go into geology. She was going to school at a community college in Las Vegas when she decided it was time for her to “come home.” The college she attended didn’t talk a lot about Native culture or the indigenous people from the area. Meninick had graduated from the Yakama Nation Tribal School, so an education without the inclusion of Native voices seemed unusual and a bit uncomfortable. When she started at Heritage, the inclusion of TEK felt so normal that it wasn’t really anything she noticed.

“It was just so much more comfortable for me here,” she said.

Last summer Meninick participated in an internship with Yakama Nation Water Resources. The department participates in educational outreach with students at the tribal school. Part of their goal is to encourage kids to explore careers in the sciences. Meninick was asked to translate a water cycle graphic into Sahaptin, the traditional language of the Yakama people, for use in their outreach materials.

“It was great to have this opportunity because it gives kids an opportunity to learn both science and our language,” she said. “A lot of this information has been handed down for generations. I believe that our people are starting to forget a lot of the stories. Bringing this to the schools brings it back to the community.”

Meninick presented the translated water cycle at the national American Indian Science and Engineering Society Conference earlier this year.

“I had a lot of people compliment me on my work, especially younger people,” she said. “They found it inspirational.”

Her work will continue to inspire future Native scientists as Water Resources use it at the tribal school for years to come.