This Is a Woman’s World

When Kim Bellamy-Thompson went into law enforcement 36 years ago, she knew she was entering a man’s world.

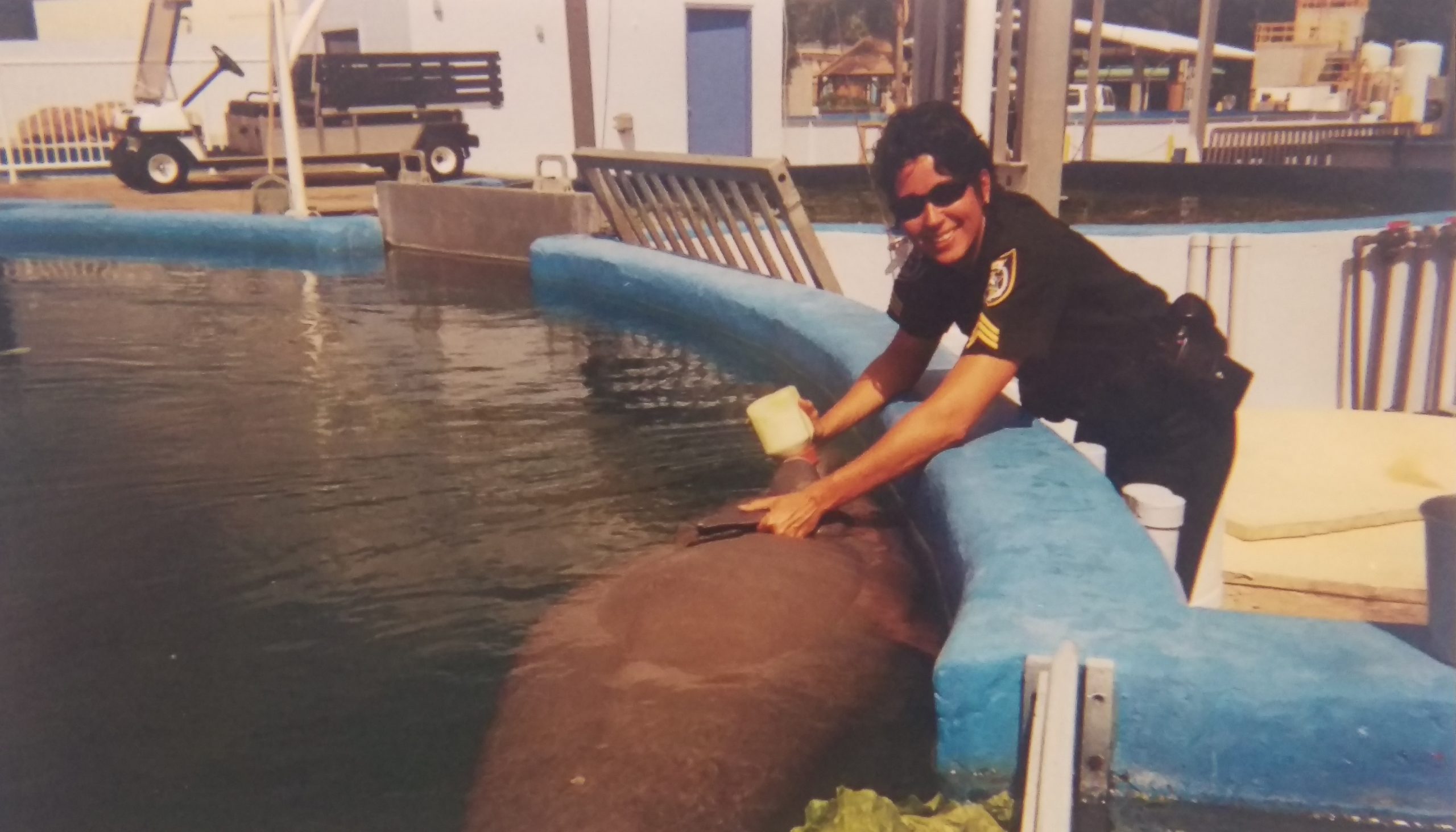

Kim Bellamy-Thompson spent 23 years working as a police officer for the Orange County Sheriff’s Office in Orlando, Florida

“You had to prove yourself,” said Bellamy- Thompson, chair of Heritage’s Criminal Justice program. It was Orange County, Florida, 1984. “I proved myself, and I went on to have a really meaningful career.”

When Sergeant First Class Syvilla Reynolds enlisted in the Army in 1989, she saw a similar challenge.

“I knew I had to work twice as hard and keep my nose to the grindstone, always driving for bigger and better things,” said Reynolds, who’s now in the physician assistant program at Heritage.

Thirty years later, Dawn Waheneka, an HU history major and Mellon Fellow, didn’t pay much attention to other people’s expectations. She entered the U.S. Navy to better herself.

“I grew from the experience, not knowing at the beginning how big it would be. I 100-percent bettered myself,” she said.

History major Dawn Waheneka constructs a wall framework for a new building at a military base in Afghanistan as part of her job as a Navy Seabee.

Times have changed for women in the military and law enforcement. There are fewer hurdles, the pay is good, career paths are solid, and there can be help with college tuition during or after service.

There are opportunities in these careers,

these women said. You do meaningful work. You overcome a myriad challenges. But most of all, you learn a lot about who you really are.

SKILLS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Throughout her career in law enforcement, Bellamy-Thompson had many assignments. She was a patrol officer. She was a narcotics agent. She investigated white-collar crimes, sex crimes and elder abuse.

She wasn’t all about arresting people, “grabbing people and throwing them on the ground.” Although that’s what’s often seen on television and in social media today, it didn’t represent her experience, she said.

What was important to Bellamy-Thompson was making a difference in people’s lives. She did it every day when she helped someone in distress while on patrol, investigated her way to the truth about who committed a crime, or helped bring an offender to justice.

Sergeant First Class Syvilla Reynolds at Camp Najaf-Adair in Oregon doing medevac loading exercises on Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters.

“Mostly, law enforcement is really smart people making sound decisions to make the community a better place,” she said.

For Bellamy-Thompson, her desire to help people – what she calls providing good “customer service” on behalf of a community – was fulfilled in her law enforcement career. She brought her care, communication skills and professionalism to a job that needed it.

Bellamy-Thompson thinks women have ways of dealing with difficult situations that come naturally to them. When the issue is one of domestic violence or sexual abuse, for example, the ‘soft skills’ that women lead with help the victim and help find a resolution.

“Instead of showing up looking stoic and militaristic, I found women typically approach a problem with a desire to resolve things. We communicate our way through issues.”

U.S. ARMY ALLOWED MEDICAL PATH

Reynolds was the kind of kid who signed up for first aid classes at summer camp. She was the kid who dragged animals home and patched them up – whether they needed it or not.

Growing up in Poulsbo, Washington, Reynolds’s grandfather was a doctor, her brother an army medic. Her decision at age 18 to join the Army and work in the operating room seemed preordained.

After leaving her law enforcement career, Bellamy-Thompson came to Heritage to help other men and women prepare for careers in law and justice.

Her choice was an unorthodox one for a woman at the time, but Reynolds said the Army-medical path was the perfect one for her.

“It really is kind of like what you see on M*A*S*H— organized chaos. It gets your adrenaline pumping. I love that.”

While enlisted in the Army, Reynolds worked with elite Forward Surgical Teams (FSTs) for deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. She now serves one weekend a month in the reserves where she’s the company first sergeant of B Company, 396th Combat Support Hospital in Vancouver, Washington.

Reynolds and the teams she works with provide medical support for injured troops once they’re back in the States. She’s also responsible for

the training and management of soldiers on the operating team.

That’s a significant amount of responsibility, proving how much things have changed for women over Reynolds’s time in the service.

“In the ‘80s, women were almost always in support roles – administrative, supply, nursing. Today, we even have women going through ranger school. Rangers are trained in combat. They lead soldiers on difficult missions,” she said.

Dawn Waheneka traded camouflage for a book bag when she enrolled at Heritage after her military service.

JOINING THE NAVY TO SEE THE WORLD

Growing up on the Yakama reservation, the furthest Waheneka had ever ventured from home was Nevada. But, at age 17, she enlisted in the U.S. Navy. A few months later, she arrived in Spain on her first deployment.

Her second was to Afghanistan, her third split between Africa and Croatia, and her fourth Japan.

“I enlisted to better myself, and to see the world,” says Waheneka. “And I did both those things.”

As a Seabee, Waheneka’s team built complexes for U.S. Marines and roads for people in rural Afghanistan. In Africa, she was on a crew that built a maternity home for the women of a small village.

She is excited about the subject of female empowerment. She feels her personal growth through her Navy experience, combined with her Heritage education, gives her the skills to be able to help her people, especially girls and young women.

“I want to take what I’ve experienced and what I’ve learned and help Yakama youth develop a more positive sense of who they are.”

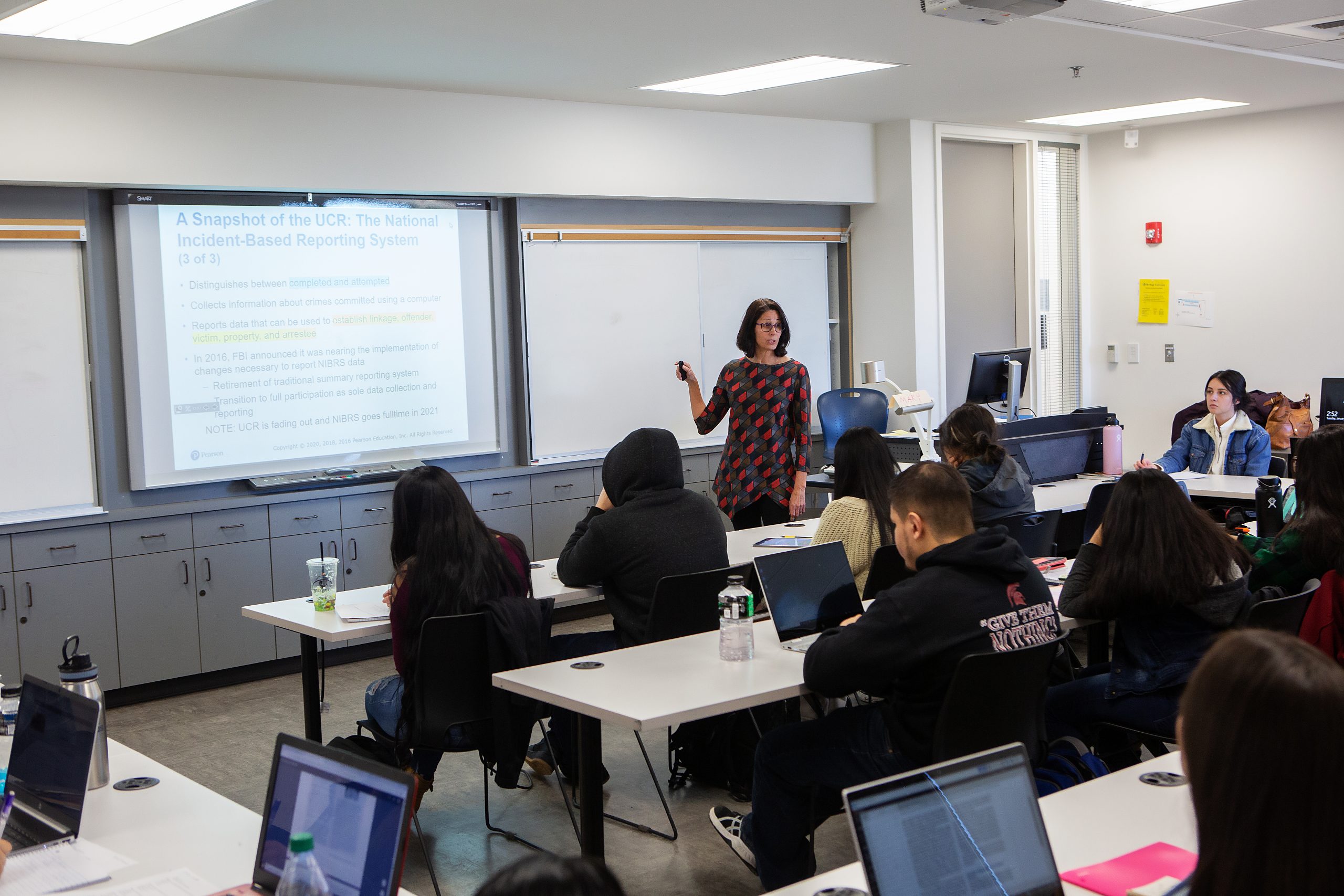

HU INTERNSHIPS START STUDENTS ON PATH

Today, women represent 15 percent of law enforcement professionals nationwide and 14 percent of active duty military. These organizations recognize the need to include women in their ranks and their leadership.

Clearly, said Bellamy-Thompson, there’s room for improvement in those numbers. But more and more, she said, both industries are working to ensure they more fully reflect the nation’s population. Bellamy-Thompson has found local agencies are very eager to create internships with the university, which has opened doors for female students.

Now, every semester, she places 10 Heritage students in internships. Their majors have included criminal justice, social work, psychology, even some of the sciences.

For 120 hours over the course of a semester, students have real-world experiences that give them a head start on the careers they’ll choose after graduation.

“I have students who are helping domestic violence victims get into shelters. There are some teaching citizenship classes as part of their internship. Often an intern moves around within the department, working with a patrol officer, then maybe in probation, then maybe in juvenile services. It all intertwines.

“One student was a biology major with a criminal justice minor who was interested in forensics. We got her an internship in the coroner’s office.”

Students who’ve had internships tend to find jobs more readily, said Bellamy-Thompson. The Yakima County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, Washington State Patrol and Washington State Department of Corrections have all hired Heritage grads who worked internships.

Women like Waheneka, Bellamy-Thompson and Reynolds paved the road for younger women today. Where they go from there is all possibility.