From Farmworker to Pharmacist – Wings Spring 2024

From Farmworker to Pharmacist

Heritage alumna’s story of sacrifice, grit, perseverance, and a dream realized

Heritage alumna Gardenia Contreras-Vazquez is very good at being first. She is the Contreras family’s first born. She was the first in her family to graduate from high school, as the valedictorian nonetheless, and the first to earn a bachelor’s degree, the first DACA student to enter Washington State University’s Pharmaceutical program, and the first to graduate. And she is the first Heritage DACA student to earn a Doctor of Pharmacy and return to her hometown to serve her community’s healthcare needs.

While being first comes with its own set of bragging rights, breaking new ground also comes with daunting obstacles that require a strong heart, steady mind and dogged commitment to your goal, traits that Gardenia has in spades.

“I was in middle school when I first started thinking I wanted to work in healthcare. I knew that my immigration status meant I would have to be creative in finding ways to make it all work. But, I never saw these obstacles as roadblocks, just challenges that I’d have to work around.”

COMING TO THE USA

Gardenia was born in Michoacán, Mexico. She doesn’t remember much about coming to the United States. She was only two years old when her parents packed up their baby girl and a few meager possessions to make the nearly 2,000-mile journey from their hometown to the US.

The move was risky. They were coming into the country without immigration credentials. However, the potential rewards far outweighed the risks they faced. In the USA, they would find better jobs. Their children could go to school, maybe even college, and they would grow up to have so many more opportunities than either parent ever had.

The young family first landed in California, where they lived for a year or two before heading north and settling in Sunnyside, Washington. Her parents went to work. Her mom went to work in the fruit industry, picking apples and cherries during the harvest and sorting fruit in warehouses. Her dad went to a dairy, milking cows 10 hours a day. While her parents worked, Gardenia and her younger brother and sister, both born after the family arrived in the United States, enjoyed a typical childhood—they went to school, played with friends, got involved in sports and clubs, all the things children do. Even though she looked and acted like every other typical American child, she was far from typical. Gardenia was undocumented.

EXPERIENCES THAT SHAPED HER

“I knew I wasn’t like other kids,” said Gardenia. “My parents always told me how important it was to behave and listen. Growing up undocumented, the fear of being deported was always in the back of your mind. You don’t dwell on it as you live your day-to-day life, but you make small adjustments so you don’t draw attention to yourself. You notice when you pull into a gas station, and there is a police car in the parking lot. You always go the speed limit and follow every small detail of the law. You kind of try to blend into the shadows.”

While she felt different, she was far from an outsider. Agriculture is the leading industry in the Yakima Valley. While technology has changed a lot about how crops are grown, harvested and processed, much of the work still depends upon manual labor. Often, that labor is done by immigrants and first-generation Americans, mostly from Mexico.

In the small town of Sunnyside, agriculture is king, directly employing more than a quarter of the community’s population. In comparison, the next largest industry is transportation and warehouses, the bulk of which is tied to ag support and employs another 14% of working adults. The nature of the industry, plus that of humans who tend to settle in areas where there is a familiarity, has shaped Sunnyside into a community where more than 80% of its population are Hispanic, and over a quarter are foreign-born. Among her peers, Gardenia’s story was very familiar.

“Growing up in Sunnyside, I had a lot of similar experiences with my classmates,” she said. “We didn’t come out directly and say, ‘Oh, I’m undocumented,’ or share our immigration status, but we knew our parents were all working in the fields and may be in similar situations. We were 13 or 14 years old, taking care of our younger siblings, cleaning the house, making dinner, helping parents with translation and filling out documents, and pretty much keeping the household running because our parents worked long, hard hours to provide for the family.”

They weren’t the only ones. From time to time, Gardenia would join her mom in the fields and sometimes work alongside her grandfather, who immigrated to the United States after Gardenia and her parents settled in Sunnyside. Though he had adjusted his status due toanother son who was a citizen, it was here, among the workers, that the teenager began to dream of becoming someone who would help people who often fell through the cracks.

“I saw my parents coming home so tired they fell asleep in their chairs. I saw the people in the fields working injured because they were too afraid to go to the doctor. If they did, they wouldn’t fill their prescriptions because the medicine was too expensive or they didn’t understand the gravity of not taking it. I knew something had to be done to help make healthcare more accessible.”

Young Gardenia’s assessment of the need was dead on. Among cultural populations in the United States, Hispanics, particularly those in immigrant households, have one of the highest rates of healthcare inequity. The reasons are as varied as the people themselves: Language and cultural barriers, socioeconomic disparity, a lack of adequate health insurance, predisposed views on healthcare and healthcare providers, immigration status, and fear of deportation are all among the influences that limit access.

While healthcare providers work to counteract these influences, such as hiring translators to assist with language barriers, making real strides involves bringing more Latinx, bilingual providers into the workforce.

“Pharmacists are both the most accessible and the most accessed member of the healthcare team. Traditionally, pharmacists have been local leaders and vital members of their community, and this remains true in rural, underserved, and smaller communities, which are usually served by caring, independent pharmacy teams,” said Joel Thome, PharmD, BCACP, associate professor.

“In areas with a significant Latinx population, Latinx pharmacists play a crucial role in bridging the cultural and language gaps, providing personalized care that respects the community’s unique health beliefs and practices. Their ability to communicate effectively in Spanish and understand the cultural nuances can enhance patient trust, adherence to medication, and ultimately, health outcomes. This is particularly important in addressing health disparities and promoting health equity in these communities.”

“In areas with a significant Latinx population, Latinx pharmacists play a crucial role in bridging the cultural and language gaps, providing personalized care that respects the community’s unique health beliefs and practices. Their ability to communicate effectively in Spanish and understand the cultural nuances can enhance patient trust, adherence to medication, and ultimately, health outcomes. This is particularly important in addressing health disparities and promoting health equity in these communities.”

UNDOCUMENTED TO DACA

Education is something that Gardenia’s parents reinforced in all their kids from the time they were very young. As children, both parents were forced to quit school and go to work to help support their families. Her mother dropped out of high school, but later earned her GED; her father never made it out of elementary school. Still, the two understood that education was vital to their children’s futures.

“My parents always told me, ‘You have to get an education. It is the one thing nobody can ever take away from you.’ They’d tell me I needed to get good grades so I could get scholarships and go to college.”

That is precisely what she did. Her parents signed her up for the Washington State College Bound program when she was in middle school. College Bound is a guaranteed scholarship for low-income students who graduate from high school and enroll in an approved college or university. Gardenia started looking for scholarships during her freshman year and explored ways to earn college credits for free while in high school. Starting her sophomore year, she enrolled in College in the Classroom, giving her college credits for some courses while meeting her high school graduation requirements. For three years, she participated in her school’s science fair. She won a prestigious scholarship to attend Ohio Wesleyan University in her first year. While that scholarship wouldn’t ultimately help her, it would only have paid half of her tuition, and covering the other half as an out-of-state student without access to federal funding assistance was unfeasible; receiving the award was all the encouragement she needed to keep moving forward. By the time she graduated from Sunnyside High School, Gardenia had received enough scholarship support to cover her undergraduate degree, including Heritage’s Dreamers Scholarship.

Finding funding for school was just the start. Being undocumented brought with it a host of other challenges that could derail her dream, like not being able to be legally employed. In 2012, then-President Barack Obama initiated Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The action protected young adults who were brought into the country as children and who met specific criteria for deportation and authorized them to work in the country for two years. The action was temporary but renewable. Gardenia’s parents immediately hired an attorney who applied for and got her DACA status. More than anything, this move was perhaps the most critical to Gardenia’s future. Without it, all that happened after earning her bachelor’s degree would not have been possible.

When Gardenia enrolled at Heritage, she knew she knew she wanted to prepare for a healthcare career, but she wasn’t sure about what exactly. It wasn’t until her senior year that she turned her attention towards a career in pharmaceuticals.

When Gardenia enrolled at Heritage, she knew she knew she wanted to prepare for a healthcare career, but she wasn’t sure about what exactly. It wasn’t until her senior year that she turned her attention towards a career in pharmaceuticals.

“Medical school was super expensive, and finding funding after undergraduate studies is difficult. I saw that WSU had a Doctor of Pharmacy program at PNWU (Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences, which is in Yakima),” she said. “I really wanted to help people in my community access better healthcare and recognized that access to medication is critical.”

FROM BACHELOR’S TO DOCTOR

Gardenia’s application to WSU was about as stellar as they come. As an undergraduate, she was a university ambassador, Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. member, and president of the Medical Sciences Club. She completed research at Heritage University on “Urinalysis: A Comparative Analysis Between Automated and Manual Method.” She graduated from Heritage magna cum laude with two degrees: a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and a Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Science, with a minor in Visual Arts. It was during the interview when Gardenia really nailed it! She spoke about her experiences growing up and how they shaped her perception of the need for people with her background in healthcare. She talked about earning her degree and staying in her hometown to work directly with the people who needed her help the most.

“After the interview, I was sitting in the waiting room when one of the interviewers came out to talk to me. She told me they loved what I had to say and wanted to offer me a position in the upcoming class but didn’t know if they were legally allowed to do so because of my status. She said they had to consult with the state attorney to ensure I could participate in the program.”

Gardenia left with what seemed like another barrier in front of her. A few weeks later, she was at Heritage in the Admissions office working when she got the call: SHE WAS IN!

“I remember stepping outside because I wasn’t sure what the state attorney had told the school. Then the person on the other line simply said, ‘How would you like to be a Coug?’ I was in shock! I couldn’t believe that this was actually happening!”

A few months later, in fall 2019, Gardenia started what would be a grueling four years of study. Just before she started, she took a part-time pharmacy assistant job at Rite Aid. Not only did this give her some insight into her future career, but it was also part of the initial requirements of the degree program. The program curriculum was extremely challenging; anything below 80% was considered a fail. Students had three tries to pass if they didn’t meet that requirement, but that would mean they had to study for a past lesson on top of studying the current lesson.

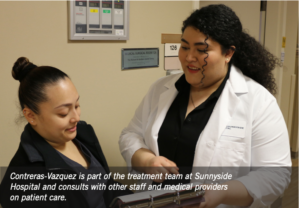

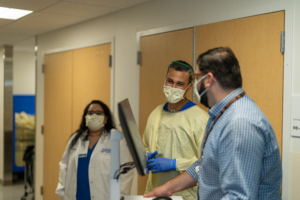

In May 2023, the former undocumented immigrant who worked alongside her family picking fruit and dreamed of a life helping people just like her live healthier lives was officially a pharmacist. She graduated with a Doctor of Pharmacy from WSU. In many ways, Gardenia’s life has come full circle. The child whose family risked everything to give her a chance at a life better than their own, the teenager who dreamed of helping farmworkers have better access to healthcare, the young woman who hit roadblocks and said, “What else,” instead of giving up is living the life she dreamed of having. Today, she is a pharmacist at Sunnyside Hospital and an essential part of the patient care team.

In May 2023, the former undocumented immigrant who worked alongside her family picking fruit and dreamed of a life helping people just like her live healthier lives was officially a pharmacist. She graduated with a Doctor of Pharmacy from WSU. In many ways, Gardenia’s life has come full circle. The child whose family risked everything to give her a chance at a life better than their own, the teenager who dreamed of helping farmworkers have better access to healthcare, the young woman who hit roadblocks and said, “What else,” instead of giving up is living the life she dreamed of having. Today, she is a pharmacist at Sunnyside Hospital and an essential part of the patient care team.

“Pharmacists are one of the most accessible medical providers in the community. Being bilingual, I can talk to patients in a language they understand so that I can fully explain their medications and treatment. I also understand the financial concerns that so many of our patients face. I help them look at available resources to pay for their medications. And, I feel like there is a level of trust that I have with patients because I come from where so many of these people are today,” she said.

“Sometimes I think, ‘Wow! I can’t believe this,’” she said. “I have my degrees. I have my career. I’m helping people in my community. It’s surreal to see how far you come. It wasn’t just me who did this. I got here because of the support of my family, my friends, the faculty/staff who believed in me, everyone around me who helped me along the way, and the scholarship donors and committees for taking a chance and believing in me. I also had four very special individuals who co-signed my loans, without whom I may not have been able to take out my graduate school loans. I definitely was blessed with a strong support system; I wouldn’t be here without them.” ![]()

DACA/DREAMERS STATE OF AFFAIRS

Gardenia’s story is very familiar on college campuses across America. Last August, the President’s Alliance on Higher Education and American Immigration Council released a report estimating that more than 408,000 undocumented students are enrolled in postsecondary education across the country. Unlike Gardenia, most do not have DACA status.

DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. It is an executive order issued by President Obama that provided temporary yet renewable protections from deportation for young people brought into the country as children. It also gave recipients the ability to work in the country legally. What it was not was a pathway to citizenship. At its height, more than 800,000 young people had DACA status.

In 2017, it was announced that DACA would be phased out. New applications for deferred status would no longer be accepted, and renewals would only be accepted through October 5 of that year. The resulting legal maneuverings from those on both sides of the issue brought forth ping-ponging injunctions that renewed, then halted, and partially reinstated the program several times over three years.

Behind the political and legal maneuvering, hundreds of thousands of young people were left in limbo. The most recent decision happened in September 2023. A federal judge in Texas ruled that DACA was unconstitutional and upheld the block to reinstate the program. Currently, no new applications are being accepted, and current recipients must reapply for protection every two years. Missing the deadline has dire consequences; the person would no longer be protected from deportation, would be unable to legally work in the US, and could not reapply. Appeals to the ruling are in the works.

While the DACA saga has been in motion, another piece of legislation has been trying to make its way through Congress. It has similar guidelines for eligibility but differs in that it provides a pathway to citizenship. That legislation is the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. At least 11 versions of the DREAM Act have been introduced to Congress in the last 20 years. The most recent iteration is the bipartisan DREAM Act 2023. This legislation would tie the pathway to citizenship for young people brought into the United States as minors to education, work, and military service and would apply to those with DACA status and those without. However, despite its bipartisan construction, it has not received enough support to become law.

As politicians continue their debates, immigrant workers, their families and the businesses and communities who depend upon them wait in uncertainty. The impact of these, or any other similar legislation, has implications that branch out much further than the undocumented person seeking legal status.

Immigrant workers play an integral role in the American economy. Some industries, like construction and agriculture, rely heavily on foreign-born workers, particularly in lower-skilled labor positions. In agriculture, estimates of how many undocumented workers are employed on farms and in the fields go as high as 50% of the labor force.

On an even larger scale, undocumented workers infuse the economy to the tune of more than a trillion dollars of spending power and nearly $10 billion in federal, state, and local taxes annually.

So, where does the current state of affairs leave undocumented students today? Coming behind the wave of DACA students who had some relief are hundreds of thousands of Dreamers whose futures are murky.

“So many of our young people are trapped in this web of uncertainty,” said Dr. Andrew Sund, president of Heritage University. “They’ve been raised here, educated here, are part of the fabric of our communities. They have great potential and a work ethic as strong as anyone’s but face daunting obstacles that block access to the resources to reach that potential.”

Sund points out that one of the most significant roadblocks is finding the money to pay for post-secondary education.Undocumented students, even those with DACA protections, do not qualify for any form of federal funding. Washington State has programs to help undocumented students pay for their education, including the Washington State College Grant and the College Bound Scholarship. Still, this funding alone isn’t nearly enough to cover college costs. Scholarships are critical to bridge the gap that is left after state funding is applied. Heritage has several scholarships that DACA and Dreamer students can qualify to receive, including the full-tuition Dreamer Scholarship. Most of these funds are made possible by contributions made to the university by generous supporters.

For those lucky enough to have DACA status, the back and forth of contrary legal decisions and worry about what will happen next adds anxiety on top of the typical day-to-day stressors of college life. Plus, the expense of legal and application fees for already cash-strapped students adds to the anxiety.

Heritage established the DACA Emergency Fund in 2017 when students were scrambling to manage expiring DACA statuses in the face of a shortened renewal application deadline. It provides financial assistance to help students cover the cost of application fees, eliminating this potential barrier.

“We want students to know there are people out there that believe in them and are here to support them,” said Sund. “It is essential that they don’t put their futures on hold and wait until elected officials in Washington DC devise a permanent solution. There are resources available and people who will help them get the education they need to secure their future.

“We need all our young people to be educated. We need them in our schools, businesses, social services, hospitals, and clinics to fill critical roles that benefit all of us. Our local, state and federal agencies benefit from the income their tax dollars bring through their employment and their increased purchasing power when they work in positions with higher wages,” he said. “Moreover, we need the stability that comes when our young people can plan for their futures with confidence and certainty.”

To help support the Dreamers Scholarship or the DACA Emergency Fund, contact the Advancement Office at 509-865-8587 or advancement@hertiage.edu. Or make your gift online at heritage.edu/giving. ![]()

SHAMEKA PHILLIPS, PH.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Washington School of Medicine/Seattle Children’s Research Institute. She is a first-generation college student who earned a Bachelor of Science in Nursing with university and nursing honors, a Master of Science in Nursing— Family Primary Care, and a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Phillips joined Heritage’s nursing faculty in 2023.

SHAMEKA PHILLIPS, PH.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Washington School of Medicine/Seattle Children’s Research Institute. She is a first-generation college student who earned a Bachelor of Science in Nursing with university and nursing honors, a Master of Science in Nursing— Family Primary Care, and a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Phillips joined Heritage’s nursing faculty in 2023. JOHN KERR teaches science and career and technical education (CTE) in the Granger School District. He has advanced proficiency in Spanish and intermediate proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. He is a Tri-Cities Regional Crystal Apple Award winner and was the ESD 123 Regional Teacher of the Year in 2011. Kerr joined Heritage’s education faculty in 2022.

JOHN KERR teaches science and career and technical education (CTE) in the Granger School District. He has advanced proficiency in Spanish and intermediate proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. He is a Tri-Cities Regional Crystal Apple Award winner and was the ESD 123 Regional Teacher of the Year in 2011. Kerr joined Heritage’s education faculty in 2022. AARON WELLING is Co-Founder & CEO of Sonar Insights, a market research and strategy consulting firm based in Richland, Wash. He graduated from Brigham Young University with a Spanish degree and a communications minor. He graduated with a master’s in business administration in international management from Thunderbird, The American Graduate School of Business. Welling joined Heritage’s business and accounting faculty in 2018.

AARON WELLING is Co-Founder & CEO of Sonar Insights, a market research and strategy consulting firm based in Richland, Wash. He graduated from Brigham Young University with a Spanish degree and a communications minor. He graduated with a master’s in business administration in international management from Thunderbird, The American Graduate School of Business. Welling joined Heritage’s business and accounting faculty in 2018. MELISSA ANDREWJESKI is the Assistant Secretary of the Women’s Prison Division for the Washington State Department of Corrections and is responsible for the division’s strategic vision and leadership. She has a bachelor’s degree from Eastern Washington University, focusing on social work and a minor in chemical dependency counseling, and a master’s degree in social work from Walla Walla University. Andrewjeski joined Heritage’s Criminal Justice faculty in 2009.

MELISSA ANDREWJESKI is the Assistant Secretary of the Women’s Prison Division for the Washington State Department of Corrections and is responsible for the division’s strategic vision and leadership. She has a bachelor’s degree from Eastern Washington University, focusing on social work and a minor in chemical dependency counseling, and a master’s degree in social work from Walla Walla University. Andrewjeski joined Heritage’s Criminal Justice faculty in 2009. JACOB CAMPBELL, PH.D., is a social worker in the special education department of the Pasco School District. He also runs his own business, Locus of Transformation, which supervises licensed social workers and provides consulting. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work from Eastern Washington University and graduated with his Ph.D. in Transformative Studies from the California Institute of Integral Studies. Campbell joined Heritage’s social work faculty in 2013.

JACOB CAMPBELL, PH.D., is a social worker in the special education department of the Pasco School District. He also runs his own business, Locus of Transformation, which supervises licensed social workers and provides consulting. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work from Eastern Washington University and graduated with his Ph.D. in Transformative Studies from the California Institute of Integral Studies. Campbell joined Heritage’s social work faculty in 2013.

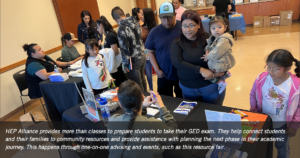

Heritage’s HEP Alliance has a remarkable success rate. Since its inception in 2004, roughly 3,000 students have earned their high school equivalent diploma. The number of students served each year fluctuates depending upon the grant parameters. Currently, it serves 100 students annually. Of these, 90% continued their education, enrolling in some form of postsecondary, technical or vocational schooling. What brings students to HEP Alliance is as varied as the people the program serves.

Heritage’s HEP Alliance has a remarkable success rate. Since its inception in 2004, roughly 3,000 students have earned their high school equivalent diploma. The number of students served each year fluctuates depending upon the grant parameters. Currently, it serves 100 students annually. Of these, 90% continued their education, enrolling in some form of postsecondary, technical or vocational schooling. What brings students to HEP Alliance is as varied as the people the program serves.

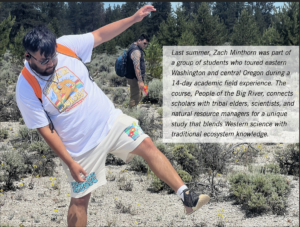

Solano and Minthorn both credit HEP for being the catalyst that got them enrolled in Heritage.

Solano and Minthorn both credit HEP for being the catalyst that got them enrolled in Heritage.

The Heritage family lost a beloved member this summer when Jim Barnhill passed away in August. He was 92. Barnhill’s connection to Heritage and its students went back to the university’s infancy. For 36 years, he and his wife Dee, who preceded him in death last year, provided philanthropic support for student scholarships and campus development. They established the Jim and Dee Barnhill Scholarship in the mid- 1990s, an endowed fund that will support students in perpetuity. Additionally, they were lead supporters of the construction of the Arts and Sciences Center, as well as the construction of five buildings built between 2015 and 2018, one of which houses The Barnhill Fireside Room, named in their honor.

The Heritage family lost a beloved member this summer when Jim Barnhill passed away in August. He was 92. Barnhill’s connection to Heritage and its students went back to the university’s infancy. For 36 years, he and his wife Dee, who preceded him in death last year, provided philanthropic support for student scholarships and campus development. They established the Jim and Dee Barnhill Scholarship in the mid- 1990s, an endowed fund that will support students in perpetuity. Additionally, they were lead supporters of the construction of the Arts and Sciences Center, as well as the construction of five buildings built between 2015 and 2018, one of which houses The Barnhill Fireside Room, named in their honor. Well-loved Yakima Valley philanthropist and long-time Heritage University supporter Marie Halverson passed away on October 21. She was 90 years old.

Well-loved Yakima Valley philanthropist and long-time Heritage University supporter Marie Halverson passed away on October 21. She was 90 years old. Tragedy struck the Heritage family on October 15 when student Aspen Hart passed away from injuries sustained in a car accident. She was 18 years old.

Tragedy struck the Heritage family on October 15 when student Aspen Hart passed away from injuries sustained in a car accident. She was 18 years old.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

On a warm late summer evening, a crowd of people gathered on the lawn at Heritage University. They stood side by side, row by row; their attention focused on a man on the stage holding the flag of México. He is from the Mexican Consulate and traveled halfway across the state of Washington to deliver El Grito de Delores, the Cry of Delores.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.

She enrolled in a local college, earned an associate degree, transferred to a nearby university, and earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology. Eventually, she worked her way to director of the HEP program, and this year, she graduated with a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership.