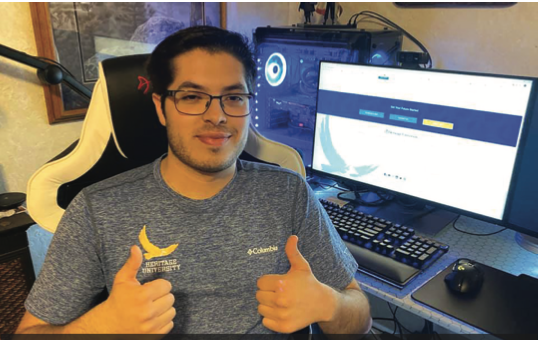

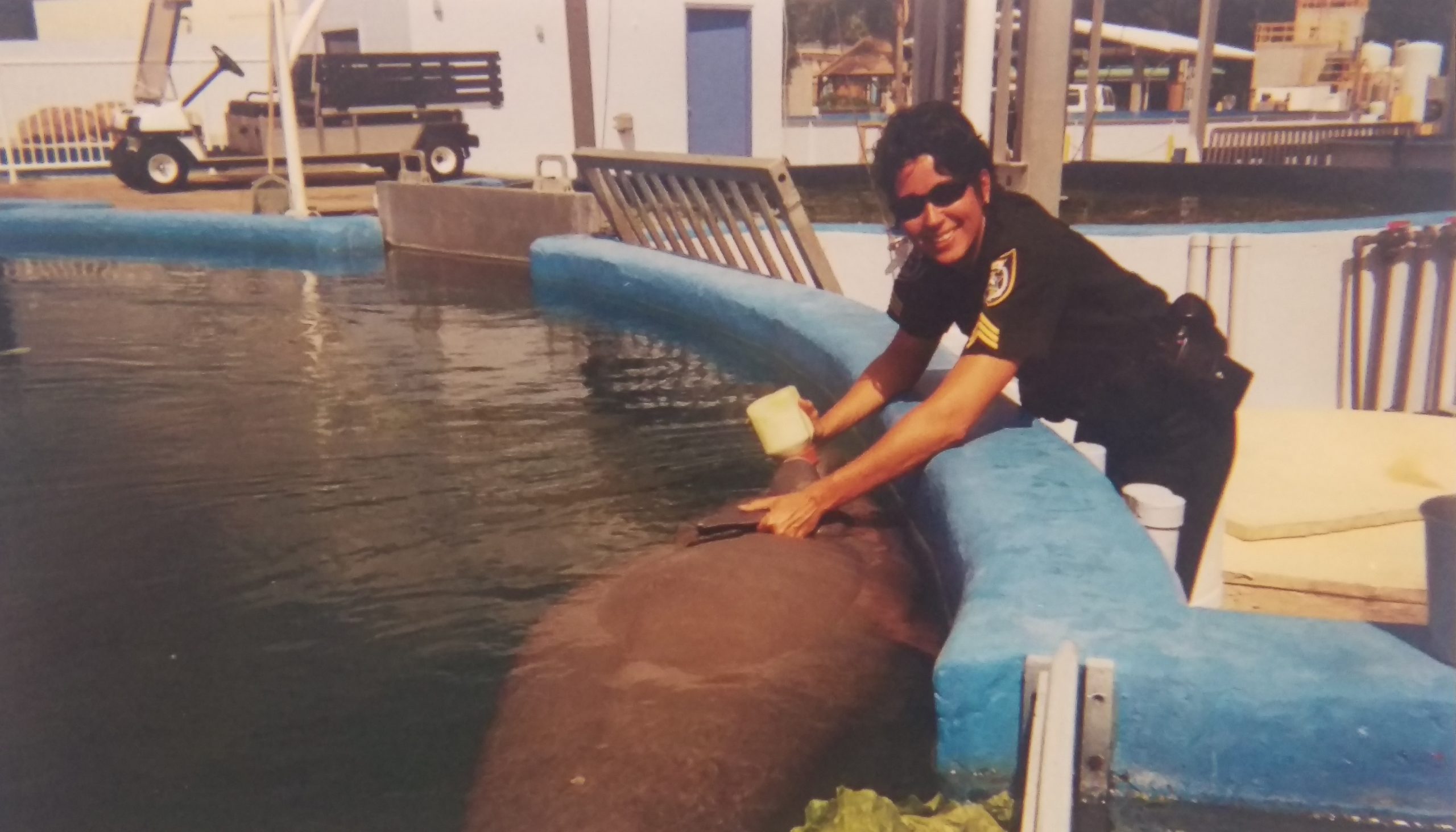

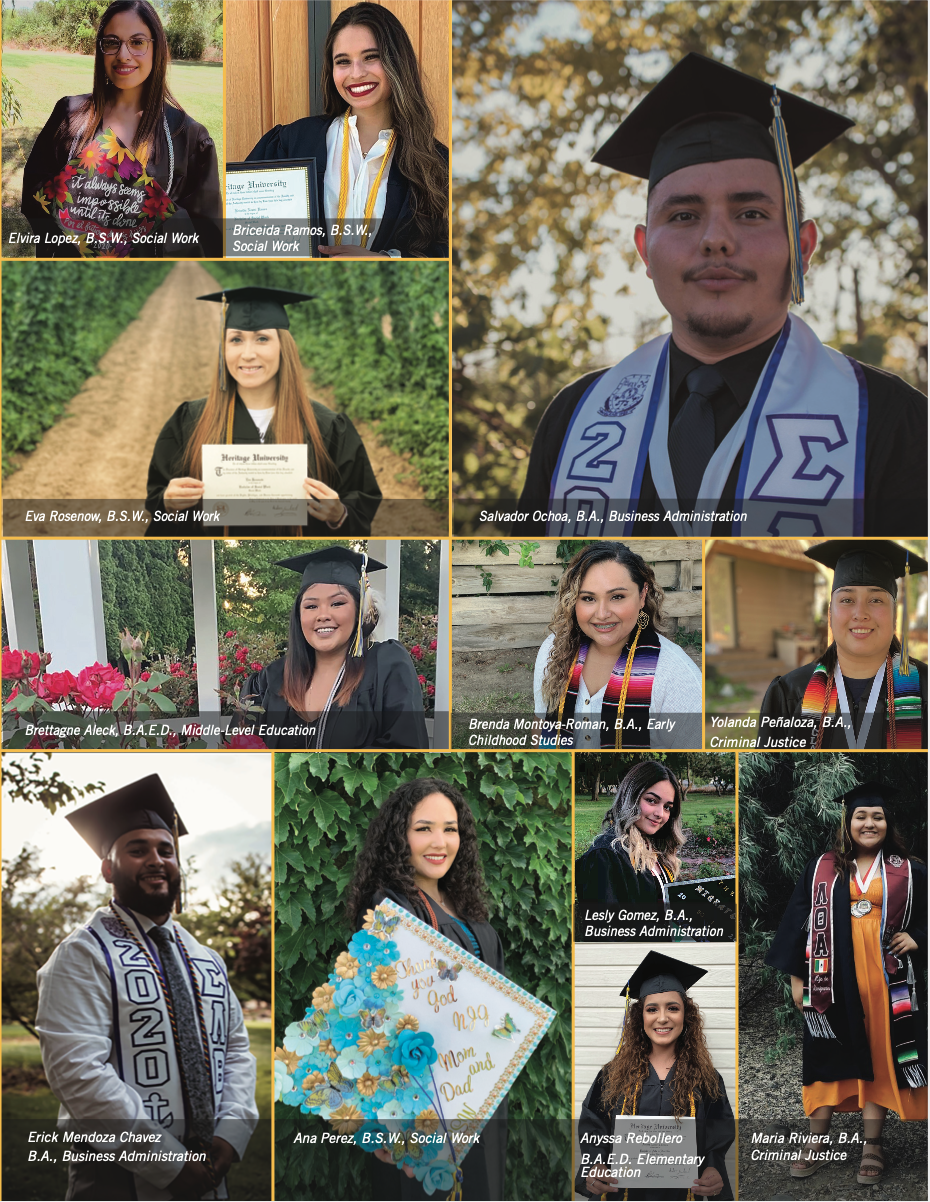

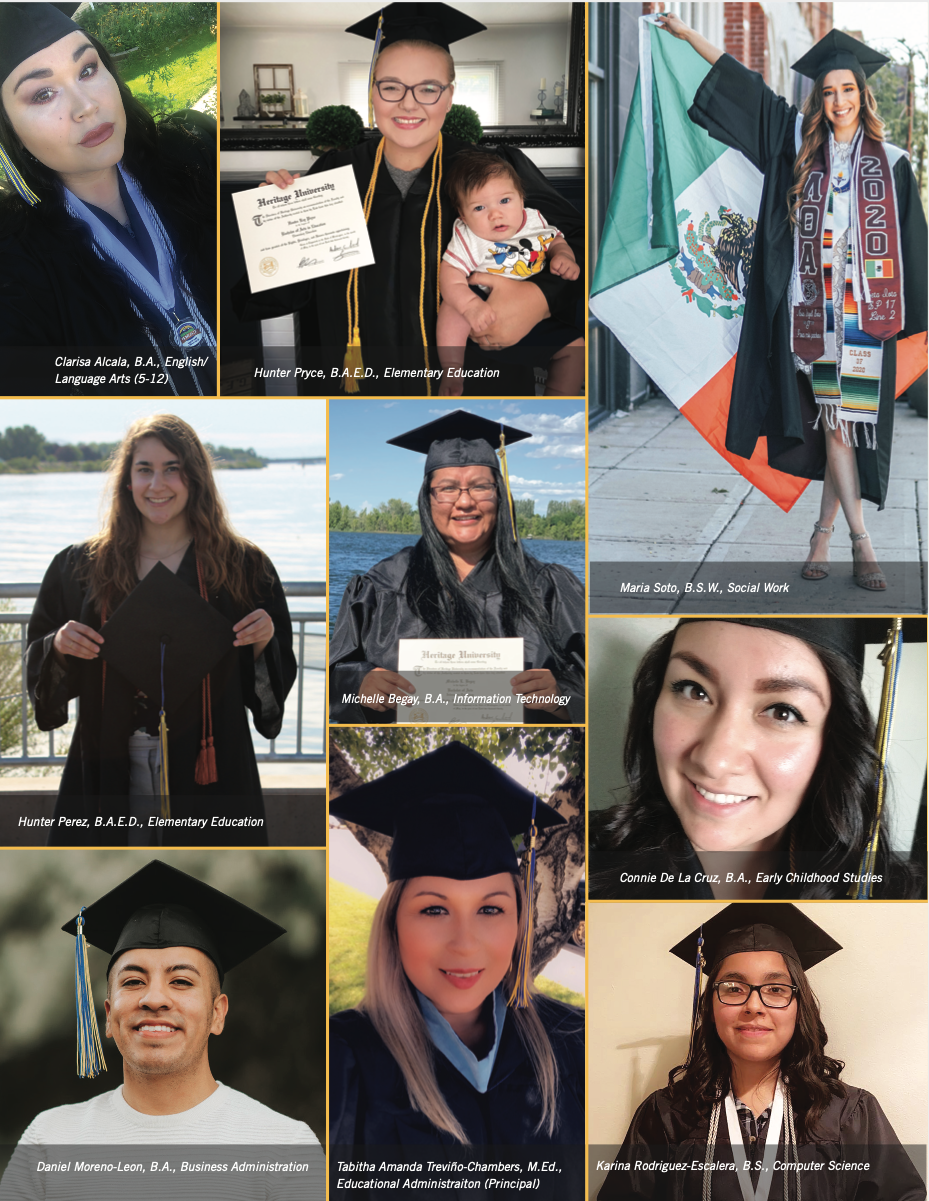

Persistence, Grit and Determination – HERITAGE CLASS OF 2020

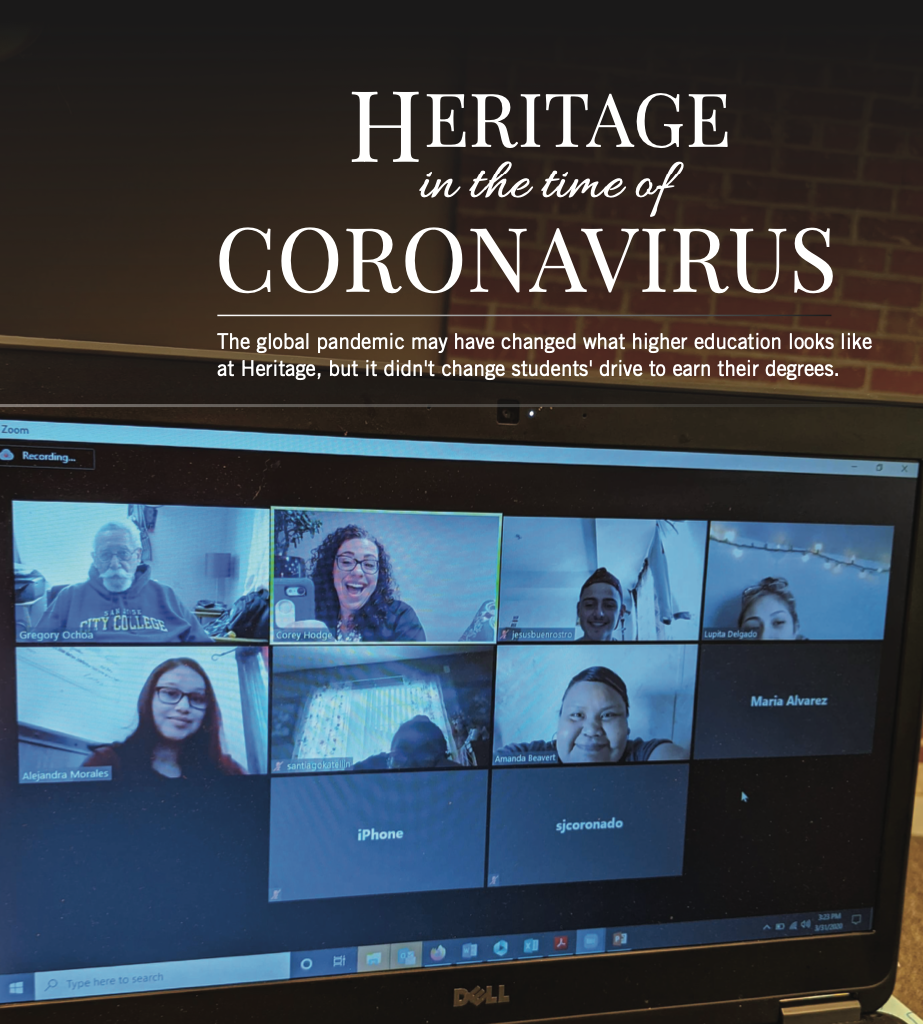

For Heritage graduating class of 2020, more than 300 strong, there was no Pomp and Circumstance, no family and friends gathering to celebrate, no crossing the stage to get their hard- earned diploma. A virus stole their moment of glory. However, it does not diminish their accomplishment in the least.

For Heritage graduating class of 2020, more than 300 strong, there was no Pomp and Circumstance, no family and friends gathering to celebrate, no crossing the stage to get their hard- earned diploma. A virus stole their moment of glory. However, it does not diminish their accomplishment in the least.

“We are always proud of our graduates. This year even more so,” said Dr. Andrew Sund, Heritage University president. “The Class of 2020 faced challenges far beyond anything we ever could imagine. They showed incredible resiliency, determination and grace as they completed their studies under the added pressure of a global pandemic.”

When COVID-19 shut down much of Washington state in mid-March, it quickly became clear that Commencement would have to be postponed. Sund made the announcement on April 1.

“It was a difficult announcement to make because we all understand the importance of Commencement. It is the most powerful opportunity for students to celebrate their accomplishments with their loved ones. It is also one of the happiest days for us, the staff and faculty. We work hard to see our graduates accomplish their goals and the spirit of celebration is present in all of us,” he said.

Sund carefully pointed out that the celebration wasn’t outright canceled.

“We will hold Commencement for the Class of 2020 as soon as it is feasible to do so,” he said, noting that the timing will depend upon the status of Yakima County in keeping with the directives of the Health Department and Governor’s Office.

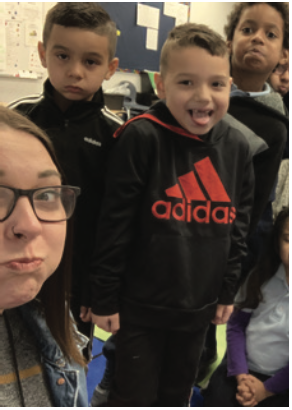

Since graduates couldn’t come to the celebration, Heritage’s Alumni Connections decided to take the celebration to them. Typically, the program welcomes graduates to their new role of alumni with a celebratory reception on the main campus and another in Pasco, Washington, on the Columbia Basin College campus for our Tri-Cities cohort in the days before Commencement. These too were canceled.

“When students graduate from Heritage, they remain a vital member of the university family,” said David Wise, vice president for Advancement and Marketing. “Their role shifts. They become mentors, advisors and ambassadors whose experiences inspire students to envision their own futures, and they build the professional network for all graduates. Alumni Connections is here to help facilitate all of this.”

Instead, the program produced custom gift boxes filled with a Heritage Alumni 2020 hoodie, a university seal embossed portfolio and a Heritage University Alumni license plate frame. Graduates who were planning on attending Commencement and who ordered their caps and gowns also received their regalia in their gift boxes.

“We realize that a hoodie or a license plate frame will never replace the experience of hearing your name called and walking across that stage, but we hope it takes away a little bit of the sting of disappointment and lets our graduates know that we care about them and are extremely proud of everything that they accomplished,” said Wise.