Alumni Connections and Class Notes

Heritage alumni welcome to your special section of Wings! Here you will find feature stories on alumni doing great things in their communities, updates on what other alums are up to in their careers and personal lives, and news from Alumni Connections about upcoming events and opportunities.

You are an important part of the university family, and we want to make sure that you are fully informed of all the great opportunities that are available to you through Alumni Connections. There are lots of great ways to stay connected:

• Like us on Facebook (facebook.com/HeritageUniversityAlumni)

• Sign up to receive Heritage’s e-newsletter HUNow.

• Visit us online at heritage.edu/alumni

Of course, the best way to stay connected is to make sure your contact information is up to date. Please be sure to let us know if your address, e-mail or phone number changes. You can submit your changes online through heritage.edu/alumni, e-mail us at alumni@heritage.edu or give us a call at (509) 865-8588.

1990

1990

Richard “Dick” Welch (M.Ed., Educational Administration with Principal Credentials) passed away on August 12, 2019. He was 74. Prior to his retirement in 1990, he was the athletic director and attendance administrator for West Valley High School.

1994

Laurence Keeler (M.Ed., Professional Development) passed away at the age of 74 on July 26, 2019. Before his retirement in 2001, he taught for 30 years in the Yakima School District.

2003

Jim Williams (MA.Ed., Professional Development) and his wife Kirsten opened the Public House of Yakima earlier this year. The Public House is an intimate restaurant and taproom that features locally made craft beers and fine wines.

2005

Suheil (Guzman) Walker (B.A., Business Administration) was hired by Anthem, Inc. to serve as the senior technical recruiter. Anthem provides health insurance to 40 million members across the United States.

2012

Mario Uribe Saldana (M.Ed., Elementary Education) is the vice principal at McLoughlin High School in Milton Freewater, Oregon.

2016

Daylen Isaac (B.S., Environmental Science) is a statistician with the Yakama Nation Fisheries. Isaac graduated from Washington State University with a master’s degree in horticulture.

2018

Aleesa Bryant (B.S., Biomedical Science) joined the USDA’s Agriculture Research Service division as a biological science technician in May.

Shahin Carter (M.S., Physician Assistant) was selected for the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance advanced practice provider fellowship in oncology and bone marrow transplant. She is one of three recent physician assistant or nurse practitioner graduates selected for the program, which operates in partnership

with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington.

Alejandra Haro (B.A., Business Administration) opened Local Beet Meal Prep, a meal preparation service that focuses on serving healthy, plant- based meals. Haro collaborated with another Yakima startup company, Healthy Eats Nutrition Services, which teaches healthy cooking using plant-based recipes.

The partners celebrated the grand opening of their retail space in July.

Michael Valdez (M.S., Physician Assistant) is a physician assistant at The Center Orthopedic & Neurosurgical Care in Bend, Oregon in the orthopedics department.

2019

Christie Fiander (B.A., Environmental Studies) is working to protect endangered species as a wildlife biologist with the Yakama Nation Environmental Restoration and Waste Management Program.

Brenda Lewis (B.A., Business Administration) is a compliance officer with the Yakama Nation Department of Revenue.

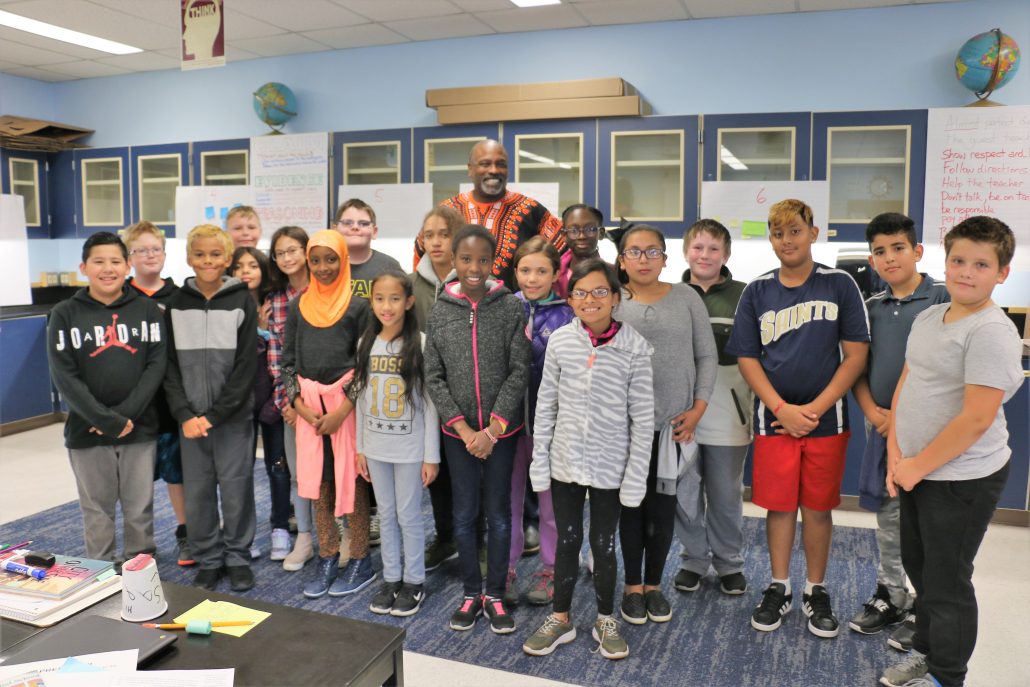

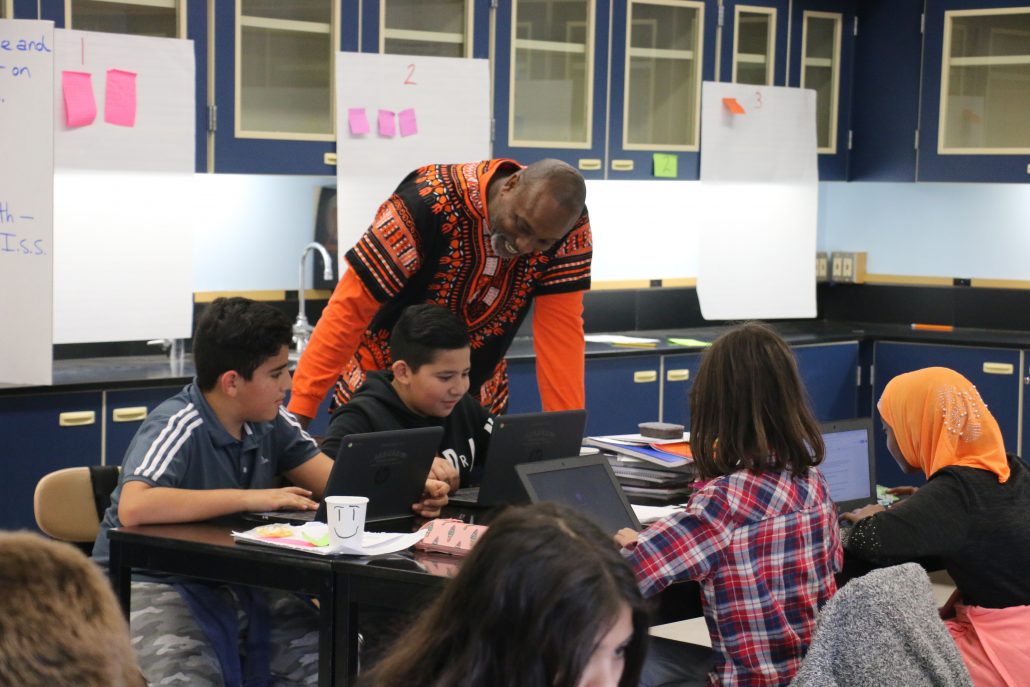

Maria Lara (B.A.Ed., Elementary Education) is teaching 6th grade English development at Captain Gray STEM Elementary School in Pasco, Washington.

Submit Your Class Notes

Send us your submission for Class Notes. It’s easy. Just visit heritage.edu/alumni, complete the submission form and upload your picture. Be sure to include a valid email address so we can contact you if we have any questions.